The terms “North Country” and “world premiere” haven’t mingled very often, but May 8, 1953 was one notable exception. It all had to do with Fort Ti, but not the one we’re all familiar with. This was Fort Ti, the movie, and it was special for several reasons. Read more

The terms “North Country” and “world premiere” haven’t mingled very often, but May 8, 1953 was one notable exception. It all had to do with Fort Ti, but not the one we’re all familiar with. This was Fort Ti, the movie, and it was special for several reasons. Read more

Adirondacks

Emancipation Weekend in the Adirondacks

](http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Emanposterewebpt1.221-300x217.png) January 1, 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and students, educators, and general public across the North Country will have the opportunity to support a New Proclamation of Freedom for the 21st century.

January 1, 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and students, educators, and general public across the North Country will have the opportunity to support a New Proclamation of Freedom for the 21st century.

On Friday 30 November and Saturday 1 December, modern-day abolitionists will gather with students, teachers and the general public concerned about human freedom and human trafficking at various venues in Saranac Lake and Lake Placid. Activities will include an art exhibition, a screening of the popular Civil War film Glory, workshops, lectures, and a closing reception following historian David Blight’s keynote address on Saturday night. (Full schedule follows.) Read more

Northern New York Survival Stories

I recently covered some pretty tough hombres from Lyon Mountain in far upstate New York. Rugged folks, for sure, but by no means had they cornered the market on regional toughness. Here are a few of my favorite stories of Adirondack and North Country resilience. Read more

I recently covered some pretty tough hombres from Lyon Mountain in far upstate New York. Rugged folks, for sure, but by no means had they cornered the market on regional toughness. Here are a few of my favorite stories of Adirondack and North Country resilience. Read more

Swedish Lyon Mountain Mining Oral History

Last week’s subject, iron miner George Davies (1892–1983) of Standish and Lyon Mountain, was a kindly gentleman with a powerful work ethic and a can-do, pioneer spirit. Interviews with him in 1981 were key to my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. Humble and matter of fact, he shared recollections from nearly 80 years earlier. Read more

Last week’s subject, iron miner George Davies (1892–1983) of Standish and Lyon Mountain, was a kindly gentleman with a powerful work ethic and a can-do, pioneer spirit. Interviews with him in 1981 were key to my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. Humble and matter of fact, he shared recollections from nearly 80 years earlier. Read more

Lyon Mountain Mines: George Davies of Clinton County

George Davies of Standish in Clinton County was about as tough an Adirondacker as you’ll find anywhere. Standish was the sister community to Lyon Mountain during its century-long run of producing the world’s best iron ore. Davies (1892–1983) was among the many old-timers I interviewed around 1980 for my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. He was kind, welcoming, and honest in describing events of long ago.

George was a good man. The stories he told me seemed far-fetched at first, but follow-up research in microfilm archives left me amazed at his accuracy recounting events of the early 1900s. His truthfulness was confirmed in articles on items like strikes, riots, injuries, and deaths.

When I last interviewed George in 1981 (he was 88), he proudly showed me a photograph of himself as Machine Shop Supervisor in the iron mines, accepting a prestigious award for safety. I laughed so hard I almost cried as he described the scene. George, you see, had to hold the award just so, hiding the fact that he had far fewer than his originally allotted ten fingers. He figured it wouldn’t look right to reveal his stubs while cradling a safety plaque.

In matter-of-fact fashion, he proceeded to tell me what happened. Taken from the book, here are snippets from our conversation as recorded in 1981: “I lost one full finger and half of another in a machine, but I still took my early March trapping run to the Springs. I had a camp six miles up the Owl’s Head Road. While I was out there, I slipped in the water and nearly froze the hand. I had to remove the bandages to thaw out my hand, and I was all alone, of course. It was just something I had to do to survive.

“When I lost the end of my second finger in an accident at work, I was back on the job in forty-five minutes. Another time I was hit on the head by a lever on a crane. It knocked me senseless for ten minutes. When I woke up, I went back to work within a few minutes. [George also pointed out that, in those days, there was no sick time, no vacation time, and no holidays. Unionization was still three decades away, and the furnace’s schedule ran around the clock.]

“When I started working down here, the work day was twelve hours per day, seven days a week, and the pay was $1.80 per day for twelve hours [fifteen cents per hour] around the year 1910. That was poor money back then. When they gave you a raise, it was only one or two cents an hour, and they didn’t give them very often.

“In one month of January I had thirty-nine of the twelve-hour shifts. You had to work thirty-six hours to put an extra shift in, and you still got the fourteen or fifteen cents per hour. It was pretty rough going, but everybody lived through it. Some people did all right back then. Of course, it wasn’t a dollar and a half for cigarettes back then [remember, this was recorded in 1981].

“Two fellows took sick at the same time, two engineers that ran the switches. They sent me out to work, and I worked sixty hours without coming home. Then the boss came out to run it and I went and slept for twelve hours. Then I returned for a thirty-six hour shift. No overtime pay, just the rate of twenty-five cents per hour.” Now THAT’s Lyon Mountain toughness.

The tough man had also been a tough kid. “When I was thirteen years old, I worked cleaning bricks from the kilns at one dollar for one thousand. On July 3rd, 1907, when I was fifteen, I accidentally shot myself in the leg. I stayed in Standish that night, and on the next day I walked to Lyon Mountain, about three miles of rough walking.”

His father was in charge of repairing the trains, and young George climbed aboard as often as he could. “I was running those engines when I was sixteen years old, all alone, and I didn’t even have a fireman. I always wanted to be on the railroad, but I had the pleasure of losing an eye when I was nine years old. I was chopping wood and a stick flew up and hit me in the eye.

“I pulled it out, and I could see all right for a while. Not long after, I lost sight in it. The stick had cut the eyeball and the pupil, and a cataract or something ruined my eye. The doctor wanted to take the eye out, but I’ve still got it. And that’s what kept me off of the railroad. That was seventy-nine years ago, in 1901.”

Next week: A few of George Davies’ remarkable acquaintances.

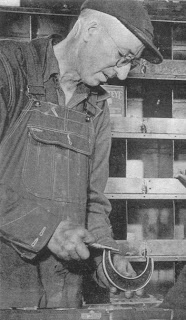

Photo: George Davies.

Lawrence Gooley has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 32 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing

Documentary Shooting At Saranac Laboratory Museum

While George Washington Carver would become known as “the peanut man,” because of his extensive research into the practical uses and agricultural advantages of peanuts, Carver’s life work and legacy went far beyond the peanut in his search for ways to “help the man farthest down,” as he put it.

While George Washington Carver would become known as “the peanut man,” because of his extensive research into the practical uses and agricultural advantages of peanuts, Carver’s life work and legacy went far beyond the peanut in his search for ways to “help the man farthest down,” as he put it.

His early years were fraught with struggle and rejection, beginning with his birth to a slave mother near the end of the Civil War. He witnessed mob lynchings, was denied admission at a white college, and yet became a well-educated scientist and teacher of national and worldwide influence and renown.

Signature Communications of Huntingtown, MD, has been engaged by the National Park Service to produce a centerpiece video for visitors to the George Washington Carver National Memorial, located at Carver’s birthplace in Diamond, MO. Titled “Struggle and Triumph: The Legacy of George Washington Carver,” this 25 minute film will be accompanied by an educational video and supplemental educational package tied to national Common Core curriculum standards.

As part of the filming process, and to augment the archival images and film available, Signature is bringing Carver’s experience and legacy to life through re-enactments of seminal experiences in his life, filmed in authentic period settings. Childhood scenes have already been filmed with actors at historic villages and farms in Missouri, as well as at Carver’s birthplace in Diamond, MO. Because the lion’s share of Carver’s lifetime of achievement occurred at Tuskegee University, the filmmakers want to reinforce the significance of his laboratory research and teaching there. Unfortunately, none of the interior settings where Carver worked at Tuskegee have been retained in their historical condition. After a wide search, Signature decided on the Saranac Laboratory Museum at Historic Saranac Lake, and will be undertaking location filming there on November 14.

Dating from 1894 – near the time when George Washington Carver was preparing to move from the Midwest to Tuskegee – the Saranac Laboratory’s white glazed brick walls, wooden cabinetry and period-accurate hood cabinet are very much of the same historical style as those of Carver’s later labs at Tuskegee. Period photographs reinforce that similarity. To round out the illusion, the filmmakers will be outfitting a professional actor with period attire to represent Carver, and are also seeking several young college age men and women to appear as supporting actors representing Carver’s African American students at Tuskegee. Acting experience is not required for these non-speaking roles, and Signature Communications will supply appropriate wardrobe as well as $100 stipend and a credit in the film. Contact: John Allen, 410-535-3477, [email protected].

Photo Caption: George Washington Carver teaching in his Tuskegee University Laboratory, c.1905. Library of Congress photo archive.

Program On Adirondack Bread, Beer Saturday

![]() Adirondack Museum Curator Hallie Bond will present a program on the history of food in the Adirondacks, particularly the connection between bread and beer. The program, called “Traditions in Bread and Beer: Lives of Adirondackers Before Modernization,” will involve discussion and displays- participants will be able to sample both ingredients and final products.

Adirondack Museum Curator Hallie Bond will present a program on the history of food in the Adirondacks, particularly the connection between bread and beer. The program, called “Traditions in Bread and Beer: Lives of Adirondackers Before Modernization,” will involve discussion and displays- participants will be able to sample both ingredients and final products.

Bond is co-writing a book about traditional food of the Adirondacks and has discovered connections between bread and beer- the two were complementary tasks for early Adirondackers. Her presentation will address how they were made before World War II and how transportation networks, particularly railroads, were established.

Bond has been a curator at the Adirondack Museum since 1987. She has curated a number of popular exhibits including “Common Threads: 150 Years of Adirondack Quilts and Comforters,” “A Paradise for Boys and Girls: Children’s Camps in the Adirondacks,” and “Boats and Boating in the Adirondacks.” She has written extensively about regional history and material culture.

The program will be held from 3 to 5 pm on November 10 at the Adirondack Interpretive Center (AIC) in Newcomb. The AIC is a branch of the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry’s Northern Forest Institute. For more information contact the AIC at 518-582-2200 ext. 11 or by email at [email protected].

Thomas William Symons: Father of Barge Canals

The first 20 years of Keeseville’s Thomas William Symons’ work as an engineer were incredibly successful. A list of his achievements reads like a career review, but he was just getting started. After a second stint in the Northwest, he returned to the east in 1895, charged with planning and designing the river and harbor works at Buffalo. He was named engineer of the 10th Lighthouse District, which included Lakes Erie and Ontario, encompassing all the waterways and lighthouses from Detroit, Michigan, to Ogdensburg, New York.

Among his remarkable projects was “a very exposed, elaborate lighthouse and fog signal” on Lake Erie, near Toledo. Grandest of all, however, was one of Thomas Symons’ signature accomplishments: planning and constructing the world’s longest breakwater (over four miles long). Built along the shores of Buffalo, it was a project that earned him considerable attention. Further improvements he brought to the city enhanced his reputation there.

Another major project talked about for years came to the forefront in the late 1890s—the possibility of a ship canal spanning New York State. The 54th Congress in 1897 commissioned a report, but the results disappointed the powerful committee chairman when Symons’ detailed analysis named a barge canal, not a ship canal, as the best option.

In 1898, New York’s new governor, Teddy Roosevelt, assigned Thomas to personally investigate and report on the state’s waterways, with emphasis on the feasibility of a barge canal to ensure it was the correct option. A concern on the federal level was national security, which was better served by Symons’ plan to run the canal across the state rather than through the St. Lawrence River to Montreal, up Lake Champlain, and down the Hudson to New York City.

Thomas’ route across New York kept the structure entirely with America’s borders. (This and many other projects were requested by the War Department, which explains the security factor.) His additional work for Roosevelt reached the same conclusion, and after extended arguments in Congress, $100 million was appropriated for canal improvements. The decision was affirmation of Thomas’ judgment and the great respect in Congress for his engineering capabilities.

In 1902, the senate noted “the conspicuous services of Major Thomas W. Symons regarding the canal problems in New York,” and that he had “aided materially in its solution.” A senate resolution cited “his able, broad-minded, and public-spirited labors on behalf of the state.”

During the canal discussions, his life had taken an unusual turn. Teddy Roosevelt had won the presidency in 1902, and in early 1903, the decision was made to replace his top military aide. Keeseville’s Thomas Symons was going to the White House.

It was sad news for Buffalo, Thomas’ home for the past eight years. At a sendoff banquet, the praise for him was effusive. Among the acknowledgments was that his work in Buffalo’s harbor had brought millions of dollars of investments and widespread employment to the city. From a business and social perspective, one speaker professed the community’s “unbounded love, affection, and admiration.” The comments were followed by an extended ovation.

For a man of Symons’ stature, some of the new duties in Washington seemed a bit out of place. Officially, he was the officer in charge of Public Buildings and Grounds of the District of Columbia, a position for which he was obviously well suited. (And, the job was accompanied by a pay raise to the level of Colonel of Engineers.)

However, Thomas was also the president’s number one military aide, making him the Master of Ceremonies for all White House functions. Every appearance by Teddy Roosevelt was planned, coordinated, and executed by Symons, his close personal friend. Depending on whom the guests were, Thomas selected the decor, music, food, and entertainment.

He became the public face of all White House events. In reception lines, it was his duty to be at the president’s side. No matter what their stature, he greeted each guest as the line progressed, and in turn introduced each guest to Roosevelt. Everyone had to go through Roosevelt’s right-hand man before meeting the president (though he actually stood to the president’s left).

He became the public face of all White House events. In reception lines, it was his duty to be at the president’s side. No matter what their stature, he greeted each guest as the line progressed, and in turn introduced each guest to Roosevelt. Everyone had to go through Roosevelt’s right-hand man before meeting the president (though he actually stood to the president’s left).

He also played a vital diplomatic role by mingling with the guests, ensuring all were seated and handled according to their importance, and allowing the President and First Lady to feel as secure as if they had planned each event themselves.

He was also the paymaster general of the White House, seeing to it that all funds appropriated for expenses were spent properly. The media regularly noted that in Teddy Roosevelt’s home, Symons was the most conspicuous person except for the president himself.

With so many responsibilities, the job of top aide to the president seemed impossibly busy, which is why Roosevelt expanded the staff from one to nine aides, all of them placed under the charge of Symons, who could then delegate much of his authority.

The only sense of controversy to arise during Thomas’ career was related to the development of New York’s barge canal, and it had nothing to do with him personally. He was the designer of the proposed system, and many felt it was critical that he stay involved in the project. But the new duties in Washington kept him very busy. Because Congress approved additional engineering employees to work under Symons, some felt it was wrong to allow Thomas to spend some of his time working on the canal project, away from his regular job.

Symons even agreed to forego the higher pay he received from the White House position in order to help with the canal. There was considerable resistance, but Roosevelt himself stepped forward, telling Congress that as governor, he had hired Thomas Symons to closely examine New York’s waterways. Thus, there was no man better suited for overseeing the $100 million expenditure.

The legislators relented, and by authority of a special act of Congress, Symons was allowed to work on the creation of New York’s barge canal system. After Roosevelt’s first term, Thomas left the White House and focused his efforts on the canal work.

In 1908, when the Chief Engineer of the Army Corps was retiring, Symons, by then a full colonel, was among the top candidates for the job. His strongest advocate was President Roosevelt, but after 37 years of service, Thomas submitted his name to the retirement list.

He remained active in the work on New York’s canals, which he monitored closely, and despite suggestions of excessive costs, the project came in well below the original estimates. He also served on the Pennsylvania Canal Commission and continued working and advising on other engineering projects.

His role in the building of America is undeniable, from New York to Washington State- the border with Mexico- the Mississippi River- Washington, D.C.- and so many other places. The world’s longest breakwater (at Buffalo) and New York’s barge canal system stand out as his major career accomplishments. And Roosevelt’s first administration took him to the highest echelons of world power for four years. He shared the p

resident’s gratitude and friendship.

Thomas Symons, trusted aide, the man Teddy Roosevelt called the “Father of Barge Canals,” died in 1920 at the age of 71. In 1943, a Liberty ship built in Portland, Oregon was named the SS Thomas W. Symons in his honor.

Photos: Colonel Thomas Williams Symons, civil engineer- a portion of the breakwater in Buffalo harbor.

Lawrence Gooley has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 24 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing.

Thomas Symons: A Noted Western Engineer

In 1847, Thomas Symons operated a book bindery in the village of Keeseville, offering ledgers, journals, receipt books, and similar products. Rebinding of materials was much in demand in those days, a service that helped expand his clientele. While Thomas, Sr., was successful in building a business, his son, Thomas, Jr., would play an important role in building a nation.

In 1847, Thomas Symons operated a book bindery in the village of Keeseville, offering ledgers, journals, receipt books, and similar products. Rebinding of materials was much in demand in those days, a service that helped expand his clientele. While Thomas, Sr., was successful in building a business, his son, Thomas, Jr., would play an important role in building a nation.

Thomas William Symons, Jr., was a Keeseville native, born there in 1849. When he was a few years old, the family moved to Flint, Michigan, where several members remained for the rest of their lives. His younger twin brothers, John and Samuel, operated Symons Brothers & Company, the second largest wholesale firm in the state. They became two of Michigan’s most prominent men in social, political, and business circles.

Thomas chose a different route, completing school and applying to the US Military Academy at West Point. After acceptance, he proved to be no ordinary student, graduating at the top of the Class of 1874. He was promoted to Second Lieutenant, Corps of Engineers, and served at Willett’s Point, about 50 miles south of West Point. After two years, he was ready for some field work, and his timing couldn’t have been better.

Symons was assigned to join the Wheeler Expedition under fellow West Point alumnus George Wheeler. The travels of explorers Lewis and Clark and Zeb Pike are better known, but the Wheeler Expedition is one of four that formed the nucleus of the US Geological Survey’s founding.

The engineers, Symons among them, not only explored, but recorded details of their findings. The land encompassing Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah was surveyed using triangulation, and more than 70 maps were created. Their studies on behalf of America’s government produced volumes on archaeology, astronomy, botany, geography, paleontology, and zoology. The possibilities of roads, railroads, agriculture, and settlement were addressed.

The experience Thomas gained during this work was invaluable. In 1878, he was promoted to First Lieutenant. In 1879, Symons was appointed Engineer Officer of the Department of the Columbia, and was promoted to captain in 1880. Similar to the work he had done under Wheeler, Thomas was now in charge of studying the area referred to as the “Inland Empire of the Pacific Northwest,” focusing on the upper Columbia River and its tributaries.

Much of the land was wilderness, and the job was not without danger. The American government was notorious for breaking treaties with Indians, and groups of surveyors in the region were driven off by angry natives who said they had never sold the rights to their land.

Symons was a surveyor, but he was also an officer of the military. Leading a company of the 21st Infantry from Portland, Oregon, into Washington, he faced off against 150 armed warriors. The situation was potentially disastrous, but Thomas listened to the concerns of the Indians, learning their histories and beliefs. Bloodshed was avoided as Symons skillfully negotiated a truce, allowing him to survey from the Snake River north to the Canadian border, unimpeded.

Much of the upper Columbia study was conducted in a small boat carrying Symons, two soldiers, and several Indians. His report provided details of the region’s geology and history, a review so thorough that it was published as a congressional document. Combined with his earlier surveys of Oregon, it made Symons the government’s number one man in the Northwest.

Whether or not his superiors agreed with him, Symons addressed the Indians’ issues in prominent magazine articles, sympathizing with their plight. Few knew the situation better than Thomas, and he freely expressed his opinions.

Besides exploring and mapping the Northwest, he chose locations for new army outposts, built roads, and carried out military duties. He also became a prominent citizen of Spokane, purchasing land from the Northern Pacific Railroad and erecting the Symons Building, a brick structure containing commercial outlets and housing units. (A third rendition of the Symons Block remains today an important historical building in downtown Spokane.)

Thomas’ proven abilities led to a number of important assignments. In 1882, he was placed on the Mississippi River Commission, taking charge of improvements on the waterway. In 1883, the Secretary of State asked Symons to lead the US side of the joint boundary commission redefining the border with Mexico. Surveying, checking and replacing border markers, and other work was conducted while averaging 30 miles per day on rough ground in intense heat. For his efforts, Thomas received formal thanks from the State Department.

He was then sent to Washington, D.C., where he worked for six years on city projects, principally the water supply, sewage system, and pavements. He also developed complete plans for a memorial bridge (honoring Lincoln and Grant) connecting Washington to Arlington, Virginia. (A modified version was built many years later.)

Symons’ next assignment took him back to familiar territory, the Northwest. Based in Portland, he was given charge of developing river and harbor facilities in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. He did primary engineering work on canals, including one in Seattle that remains a principal feature of the city, and planned the tideland areas for Ballard, Seattle, and Tacoma harbors. Seattle’s present railroad lines and manufacturing district were included in planning for the famed harbor facilities.

On the Pacific coast, Thomas’ work on the world-renowned jetty works at the mouth of the Columbia River was featured in Scientific American magazine. He also provided the War Department with surveys and estimates for harbor construction at Everett, Washington.

Next week: Even bigger and better things, including historic work in New York State.

Photos: Thomas Williams Symons, engineer– Modern version of the Symons Block in Spokane, Washington.Lawrence Gooley has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 24 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing.

St. Lawrence Co Historical Society Annual Meeting

Lisbon, New York encompassed all of the land that became St. Lawrence County when the town was created in 1801. At that time the Town of Lisbon was part of Clinton County, and the county of St. Lawrence was not created until the following year, 1802.

Lisbon’s history is the focus of the St. Lawrence County Historical Association’s 65th Annual Meeting at the Lisbon Wesleyan Church Fellowship Hall, 48 Church St., Lisbon on Saturday, November 3rd from 11 a.m. -2 p.m. The public is invited and you do not have to be a member of the SLCHA to attend. Read more