The Churubusco Live-In, planned as the 1970 sequel to the historic Woodstock concert of 1969, was in deep trouble. The town of Clinton, which included Churubusco, sought legal help to shut the event down. J. Byron O’Connell, an outstanding trial attorney, was bombastic at times, and his aggressive quotes [if long-haired people came to the village, “they’re just liable to get shot”] appeared in major newspapers in Boston, New York, and elsewhere. As Churubusco’s representative, he sought to derail the concert and preserve the hamlet’s quiet, rural life, while the promoters, Hal Abramson and Raymond Filiberti, fought back. Read more

The Churubusco Live-In, planned as the 1970 sequel to the historic Woodstock concert of 1969, was in deep trouble. The town of Clinton, which included Churubusco, sought legal help to shut the event down. J. Byron O’Connell, an outstanding trial attorney, was bombastic at times, and his aggressive quotes [if long-haired people came to the village, “they’re just liable to get shot”] appeared in major newspapers in Boston, New York, and elsewhere. As Churubusco’s representative, he sought to derail the concert and preserve the hamlet’s quiet, rural life, while the promoters, Hal Abramson and Raymond Filiberti, fought back. Read more

Clinton County

The Churubusco Live-In: Clinton Countys Woodstock

We’ve all heard of Woodstock at one time or another—that famous (or infamous) concert held in August 1969. It was scheduled at different venues, but the final location was actually in Bethel, New York, about 60 miles from Woodstock. For many who lived through three major homeland assassinations, the Vietnam War, and the racial riots of the turbulent 1960s, Woodstock was an event representing peace, love, and freedom. It’s considered a defining moment of that generation, and a great memory for those who attended (estimated at 400,000). Read more

We’ve all heard of Woodstock at one time or another—that famous (or infamous) concert held in August 1969. It was scheduled at different venues, but the final location was actually in Bethel, New York, about 60 miles from Woodstock. For many who lived through three major homeland assassinations, the Vietnam War, and the racial riots of the turbulent 1960s, Woodstock was an event representing peace, love, and freedom. It’s considered a defining moment of that generation, and a great memory for those who attended (estimated at 400,000). Read more

Ulster County Desperado: Big Bad Bill Monroe

Americans are captivated with outlaws. Our history is filled with those colorful characters who bent the law to fit their own ends, from Jesse James to Al Capone.

Newspapers fed this fascination by following every move of many of these individuals. They were given curious names such as “The Kid,” “Gyp the Blood,” or in the case of Capone, “Scarface.” Many people do not know that a small hamlet in Ulster County had its own outlaw, known as “Big Bad” Bill Monroe. He was also identified as the “Gardiner Desperado.” Read more

Swedish Lyon Mountain Mining Oral History

Last week’s subject, iron miner George Davies (1892–1983) of Standish and Lyon Mountain, was a kindly gentleman with a powerful work ethic and a can-do, pioneer spirit. Interviews with him in 1981 were key to my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. Humble and matter of fact, he shared recollections from nearly 80 years earlier. Read more

Last week’s subject, iron miner George Davies (1892–1983) of Standish and Lyon Mountain, was a kindly gentleman with a powerful work ethic and a can-do, pioneer spirit. Interviews with him in 1981 were key to my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. Humble and matter of fact, he shared recollections from nearly 80 years earlier. Read more

Lyon Mountain Mines: George Davies of Clinton County

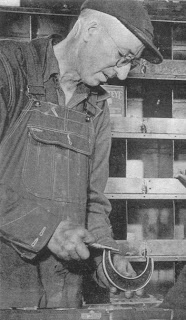

George Davies of Standish in Clinton County was about as tough an Adirondacker as you’ll find anywhere. Standish was the sister community to Lyon Mountain during its century-long run of producing the world’s best iron ore. Davies (1892–1983) was among the many old-timers I interviewed around 1980 for my second book, Lyon Mountain: The Tragedy of a Mining Town. He was kind, welcoming, and honest in describing events of long ago.

George was a good man. The stories he told me seemed far-fetched at first, but follow-up research in microfilm archives left me amazed at his accuracy recounting events of the early 1900s. His truthfulness was confirmed in articles on items like strikes, riots, injuries, and deaths.

When I last interviewed George in 1981 (he was 88), he proudly showed me a photograph of himself as Machine Shop Supervisor in the iron mines, accepting a prestigious award for safety. I laughed so hard I almost cried as he described the scene. George, you see, had to hold the award just so, hiding the fact that he had far fewer than his originally allotted ten fingers. He figured it wouldn’t look right to reveal his stubs while cradling a safety plaque.

In matter-of-fact fashion, he proceeded to tell me what happened. Taken from the book, here are snippets from our conversation as recorded in 1981: “I lost one full finger and half of another in a machine, but I still took my early March trapping run to the Springs. I had a camp six miles up the Owl’s Head Road. While I was out there, I slipped in the water and nearly froze the hand. I had to remove the bandages to thaw out my hand, and I was all alone, of course. It was just something I had to do to survive.

“When I lost the end of my second finger in an accident at work, I was back on the job in forty-five minutes. Another time I was hit on the head by a lever on a crane. It knocked me senseless for ten minutes. When I woke up, I went back to work within a few minutes. [George also pointed out that, in those days, there was no sick time, no vacation time, and no holidays. Unionization was still three decades away, and the furnace’s schedule ran around the clock.]

“When I started working down here, the work day was twelve hours per day, seven days a week, and the pay was $1.80 per day for twelve hours [fifteen cents per hour] around the year 1910. That was poor money back then. When they gave you a raise, it was only one or two cents an hour, and they didn’t give them very often.

“In one month of January I had thirty-nine of the twelve-hour shifts. You had to work thirty-six hours to put an extra shift in, and you still got the fourteen or fifteen cents per hour. It was pretty rough going, but everybody lived through it. Some people did all right back then. Of course, it wasn’t a dollar and a half for cigarettes back then [remember, this was recorded in 1981].

“Two fellows took sick at the same time, two engineers that ran the switches. They sent me out to work, and I worked sixty hours without coming home. Then the boss came out to run it and I went and slept for twelve hours. Then I returned for a thirty-six hour shift. No overtime pay, just the rate of twenty-five cents per hour.” Now THAT’s Lyon Mountain toughness.

The tough man had also been a tough kid. “When I was thirteen years old, I worked cleaning bricks from the kilns at one dollar for one thousand. On July 3rd, 1907, when I was fifteen, I accidentally shot myself in the leg. I stayed in Standish that night, and on the next day I walked to Lyon Mountain, about three miles of rough walking.”

His father was in charge of repairing the trains, and young George climbed aboard as often as he could. “I was running those engines when I was sixteen years old, all alone, and I didn’t even have a fireman. I always wanted to be on the railroad, but I had the pleasure of losing an eye when I was nine years old. I was chopping wood and a stick flew up and hit me in the eye.

“I pulled it out, and I could see all right for a while. Not long after, I lost sight in it. The stick had cut the eyeball and the pupil, and a cataract or something ruined my eye. The doctor wanted to take the eye out, but I’ve still got it. And that’s what kept me off of the railroad. That was seventy-nine years ago, in 1901.”

Next week: A few of George Davies’ remarkable acquaintances.

Photo: George Davies.

Lawrence Gooley has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 32 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing

St. Lawrence Co Historical Society Annual Meeting

Lisbon, New York encompassed all of the land that became St. Lawrence County when the town was created in 1801. At that time the Town of Lisbon was part of Clinton County, and the county of St. Lawrence was not created until the following year, 1802.

Lisbon’s history is the focus of the St. Lawrence County Historical Association’s 65th Annual Meeting at the Lisbon Wesleyan Church Fellowship Hall, 48 Church St., Lisbon on Saturday, November 3rd from 11 a.m. -2 p.m. The public is invited and you do not have to be a member of the SLCHA to attend. Read more

Bryan O’Byrne: From Plattsburgh to Hollywood

In late July, 1941, a young Plattsburgh boy received permission from his parents to visit the movie house just a few blocks away. Hours later, he had not returned home, and Mom and Dad hit the streets in search of their missing son. Soon they were at the Plattsburgh Police Station, anxiously seeking help. Two patrolmen were immediately put on the case, which, unlike so many stories today, had a happy ending.

In late July, 1941, a young Plattsburgh boy received permission from his parents to visit the movie house just a few blocks away. Hours later, he had not returned home, and Mom and Dad hit the streets in search of their missing son. Soon they were at the Plattsburgh Police Station, anxiously seeking help. Two patrolmen were immediately put on the case, which, unlike so many stories today, had a happy ending.

The two policemen obtained keys to the theater building and began searching the interior. There, curled up in his seat near the front row, little Bryan Jay O’Byrne was fast asleep. He later explained that he enjoyed the movie so much, he decided to stay for the second showing and must have drifted off into dreamland. When the theater closed for the night, no one had seen the young boy lying low in his seat.

Perhaps no one knew it then, but that amusing incident was a harbinger of things to come. Bryan O’Byrne was born to Elmer and Bessie (Ducatte) O’Byrne of Plattsburgh on February 6, 1931. Life in the O’Byrne home may have been difficult at times. Six years earlier, Bryan’s older sister was born at the very moment Elmer was being arraigned in Plattsburgh City Court on burglary and larceny charges.

Still, the family managed to stay together, and after attending St. Peter’s Elementary School and Plattsburgh High, Bryan went on to graduate from the State University Teacher’s College at Plattsburgh. After stints in the army and as an elementary school teacher, he pursued acting, studying at the Stella Adler Studio.

Still, the family managed to stay together, and after attending St. Peter’s Elementary School and Plattsburgh High, Bryan went on to graduate from the State University Teacher’s College at Plattsburgh. After stints in the army and as an elementary school teacher, he pursued acting, studying at the Stella Adler Studio.

He appeared on Broadway with Vivian Leigh in “Duel of Angels” (the run was cut short after five weeks due to the first actors’ strike in forty years). Other jobs followed, but he soon surfaced in a new, increasingly popular medium: television.

In the early 1960s, Bryan began appearing in television series, becoming one of the best-known character actors in show business. Most people recognized his face from numerous bit parts he played in television and in movies, but few knew his name. That is true of many character actors, but ironically, in O’Byrne’s case, it was that very anonymity which brought him fame.

It all took place in the 1966–67 television season with the launch of a show called Occasional Wife. The plot line followed the story of an unmarried junior executive employed by a baby food company. The junior executive’s boss felt that, since they were selling baby food, it would be wise to favor married men for promotions within the company.

So, the junior executive concocted a plan with a female who agreed to serve as his “occasional wife.” He put her on salary and got her an apartment two floors above his own. Hilarity ensued as a variety of situations in each episode had them running up and down the fire escape to act as husband and wife. This all happened to the obvious surprise and bemusement of a man residing on the floor between the two main players. That man was played by Bryan O’Byrne.

O’Byrne’s character had no name and no speaking lines, but he became the hit of the show. Usually he was engaged in some type of activity that ended up in shambles as he watched the shenanigans. The audience loved it. The show’s writers had such fun with the schtick that O’Byrne became somewhat of a sensation. His expert acting skills made the small part into something much bigger.

Eventually, in early 1967, a nationwide contest was held to give the “Man in the Middle” an actual name. Much attention was heaped on O’Byrne, but the high didn’t last for long. Occasional Wife went the way of many other promising comedies that were built on a certain premise, but were not allowed to develop. It survived only one season.

O’Byrne’s career continued to flourish. Among his repeating roles was that of CONTROL Agent Hodgkins in the hit comedy series Get Smart, starring Don Adams and Barbara Feldon. Over the years, O’Byrne remained one of Plattsburgh’s best-kept secrets, appearing in 45 television series, 22 movies, and several Disney productions.

Among those television series were some high-profile shows and many of the all-time greats: Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Batman, Ben Casey, Get Smart, Gunsmoke, I Dream of Jeannie, Maude, Happy Days, Maverick, Murder She Wrote, My Three Sons, Perry Mason, Rawhide, Sanford and Son, The Big Valley, The Bill Cosby Show, The Bob Newhart Show, The Lucy Show, The Munsters, The Partridge Family, The Untouchables, and Welcome Back Kotter.

Advertisers discovered the appeal of Bryan’s friendly face, and he was cast in more than two hundred television commercials. His experience in multiple fields and his love and understanding of the intricacies of performing led to further opportunities. He became an excellent acting coach. Among those he worked with, guided, or mentored were Bonnie Bedelia, Pam Dawber, Nick Nolte, Lou Diamond Phillips, Jimmy Smits, and Forest Whittaker.

Writer Janet Walsh, a friend of O’Byrne’s since the early 1980s, noted that, early on, he recognized the talent of young Nick Nolte. According to Walsh, “Nick slept on Bryan’s couch for a year. Bryan cast him in his production of The Last Pad, and that launched Nick’s career.”

Besides working as an acting coach for the prestigious Stella Adler Academy, O’Byrne also served on the Emmy Nominating Committee in Los Angeles. He spent nearly forty years in the entertainment business, working with many legendary stars, including Lucille Ball, Clint Eastwood, Alfred Hitchcock, and John Wayne. His television resume covers many of the best-known, most-watched series ever. And through it all, he remained a nice, unpretentious man.

Quite the journey for a ten-year-old movie fan from Plattsburgh.

Photos: Bryan Jay O’Byrne- Bryan O’Byrne and Vivian Leigh- Michael Callan, Bryan O’Byrne, and Patricia Hart from Occasional Wife.

Lawrence Gooley has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 24 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing.

Battle of Plattsburgh: Countdown to Invasion (Sept 11)

On September 11, 1814, the American and British naval squadrons on Lake Champlain engage in a long awaited duel to the death, culminating in a decisive American victory.

On September 11, 1814, the American and British naval squadrons on Lake Champlain engage in a long awaited duel to the death, culminating in a decisive American victory.

Owing to the masterful strategic planning of Commodore Thomas Macdonough, the American fleet is able to defend Plattsburgh Bay and defeat the Royal Navy following a fierce 2 1/2 hour battle, the largest of the entire War.

On land, the British commander, General Sir George Prevost makes a monumental blunder when he allows his troops to wait for an hour before commencing the land attack while they finish breakfast. What should have been a simultaneous naval and land assault became delayed and although Prevost’s ground forces succeed in crossing the Saranac River at Pike’s Cantonment, a mile and a half above Plattsburgh, by this time, the naval battle had been decided.

Believing his forces could not hold Plattsburgh without naval superiority on the Lake, Prevost quickly issued orders to his commanders to withdraw. This order was met with shock and frustration by his veteran Generals, who clearly knew a land victory over the meager American Army and Militia was easily within their grasp…-The grand British master plan of invasion from the north had been halted at Plattsburgh.

This Battle of Plattsburgh Countdown to Invasion fact is brought to you by the Greater Adirondack Ghost and Tour Company. If you enjoyed this fascinating snippet of North Country history, find them on Facebook

Battle of Plattsburgh: Countdown to Invasion (Sept 6)

On September 6, 1814, British and American forces finally collided with deadly effect just north of Plattsburgh, New York.

On September 6, 1814, British and American forces finally collided with deadly effect just north of Plattsburgh, New York.

First contact between a party of New York State Militia and the advance of the British right wing took place in Beekmantown with the Militia withdrawing in great disarray towards Culver Hill.

At the Hill, U.S. Regulars under Major John E. Wool were able to rally some of these men and made a short but heated fight before retiring in the face of the steadily advancing column.

Another stand was made at Halsey’s Corners with the aid of two six pound field guns brought up by Captain Leonard, but after firing only three rounds at the head of the British line, again the Americans were pushed back. On the “State Road” (Route 9 North) the left wing of the British advance had been hampered by obstructions and swampy terrain, but in short order they gained the crossing at the Dead Creek Bridge (Scomotion Creek) and were on their way into town.

Greatly outnumbered, the American units retreated across the Saranac River while the British took up positions in buildings throughout the town. The American Commander, General Alexander Macomb ordered hot shot to be fired into many of these structures and by nightfall, 15 buildings were burning brightly, including the Clinton County courthouse. It was the deadliest day of the entire siege, with 45 American and between 200 and 300 British killed or wounded…-

This Battle of Plattsburgh Countdown to Invasion fact is brought to you by the Greater Adirondack Ghost and Tour Company. If you enjoyed this fascinating snippet of North Country history, find them on Facebook

Battle of Plattsburgh: Countdown to Invasion (Sept 5)

On September 5, 1814, the massive British Army advancing on Plattsbugh again continued its march south after strategically splitting into two large groups, known as the left and right wing. The right wing of the British Army marched on a route through West Chazy before encamping about two miles north of Beekmantown Corners.

On September 5, 1814, the massive British Army advancing on Plattsbugh again continued its march south after strategically splitting into two large groups, known as the left and right wing. The right wing of the British Army marched on a route through West Chazy before encamping about two miles north of Beekmantown Corners.

The left wing took the “State Road” (present day Route 9 North) and advanced as far as Sampson’s Tavern (Ingraham) where they made camp. The American forces awaiting the enemy’s arrival on the Beekmantown Road was steadily being increased by the arrival of New York State Militia, streaming in from Clinton and Essex Counties, and 250 U.S. Regulars under Major John E. Wool

The photograph shows Major Wool in 1850, by which time he was a Brigadier General. He went on to serve in the American Civil War and at 77 years of age, was the oldest active duty General on either side. He died in 1869 and is buried in Troy, New York.

This Battle of Plattsburgh Countdown to Invasion fact is brought to you by the Greater Adirondack Ghost and Tour Company. If you enjoyed this fascinating snippet of North Country history, find them on Facebook