From the launch of Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential campaign with a speech at Cooper Union through the unprecedented outpouring of grief at his funeral procession in 1865, New York City played a surprisingly central role in the career of the sixteenth President—and Lincoln, in turn, had an impact on New York that was vast, and remains vastly underappreciated.

From the launch of Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential campaign with a speech at Cooper Union through the unprecedented outpouring of grief at his funeral procession in 1865, New York City played a surprisingly central role in the career of the sixteenth President—and Lincoln, in turn, had an impact on New York that was vast, and remains vastly underappreciated.

Now, for the first time, a museum exhibition will trace the crucial relationship between America’s greatest President and its greatest city, when the New-York Historical Society presents Lincoln and New York, from October 9, 2009 through March 25, 2010. The culminating presentation in the Historical Society’s Lincoln Year of exhibitions, events and public programs, this extraordinary display of original artifacts, iconic images and highly significant period documents is the Historical Society’s major contribution to the nation’s Lincoln Bicentennial. Lincoln and New York has been endorsed by the U.S. Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.

Serving as chief historian for Lincoln and New York and editor of the accompanying catalogue is noted Lincoln scholar and author Harold Holzer, co-chairman of the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. He has also organized the Historical Society’s year-long Lincoln Series of public conversations and interviews. Serving as curator is Dr. Richard Rabinowitz, president of American History Workshop and curator of the exhibitions Slavery in New York and New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War at the New-York Historical Society.

Lincoln and New York brings to life the period between Lincoln’s decisive entrance into the city’s life at the start of the 1860 Presidential campaign to his departure from it in 1865 as a secular martyr. During these years, the policies of the Lincoln administration damaged and then re-built the New York economy, transforming the city from a thriving port dependent on trade with the slave-holding South into the nation’s leading engine of financial and industrial growth- support and opposition to the President flared into a virtual civil war within the institutions and on the streets of New York, out of which emerged a pattern of political contention that survives to this day.

To begin this story, visitors follow the prairie lawyer eastward to his rendezvous with “the political cauldron” of New York in the winter of 1860. Visitors will learn something of his background and of the rapidly accelerating political crisis that had brought him to the fore: the battle over the extension of slavery into the western territories.

Then, in the six galleries that follow, visitors will discover the interconnections between these two unlikely partners: the ambitious western politician with scant national experience, and the sophisticated eastern metropolis that had become America’s capital of commerce and publishing.

Campaign (1859—1860) immerses visitors in the sights and sounds of the city, then the fastest-growing metropolis in the world, while re-creating Lincoln’s entire visit in February 1860 when his epoch-making address at the Cooper Union and the photograph for which he posed that same day together launched his national career. The displays will cast new light on the lecture culture of the antebellum city, the political divisions within its Republican organization, the strength of its publishing industry and the bustling, somewhat alien urban community that Lincoln encountered. The video re-creation of Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech, produced on site with acclaimed actor Sam Waterston’s vivid rendering of Lincoln’s arguments, brings that crucial evening to life. Visitors will re-enact for themselves how Lincoln posed for New York’s—and the nation’s—leading photographer, Mathew Brady, whose now-iconic photograph began the reinvention of Lincoln’s public image. As Lincoln himself said, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President.”

Objects on view will include the telegram inviting Lincoln to give his first Eastern lecture, the lectern that he used at Cooper Union, the widely distributed printed text of his speech, photographic and photo-engraving equipment from this era and torches that were carried by pro-Lincoln “Wide Awakes” at their great October 6 New York march. Also on view will be a panoply of political cartoons and editorial commentary generated in New York that established “Honest Abe” and the “Railsplitter” as a viable and virtuous candidate, but concurrently began the tradition of anti-Lincoln caricature by introducing Lincoln as a slovenly rustic, reluctant to discuss the hot-button slavery issue but secretly favoring the radical idea of racial equality.

The next gallery, Public Opinions (1861—62), registers the gyrating fortunes of the Lincoln Administration’s first year among New Yorkers—especially the editors and publishers of the city’s 175 daily and weekly newspapers and illustrated journals, who wielded unprecedented power. In the wake of his election, and the secession of the Southern states, the New York Stock Exchange had plummeted and New York harbor was stilled. Payment of New York’s huge outstanding debts from Southern planters and merchants ceased, and bankruptcies abounded.

Scarcely one docked ship hoisted the national colors to greet the new President-Elect in February 1861 when he visited on his way to Washington and the inauguration, and eyewitness Walt Whitman described his welcome along New York’s streets as “ominous.” Mayor Fernando Wood proposed that the city declare its independence from both the Union and the Confederacy and continue trading with both sides. Even New Yorkers unwilling to go that far desperately tried to find compromises with the South that in their words, “would avert the calamity of Civil War.”

Just two months later, though, in the wake of the attack on Fort Sumter, it suddenly appeared that every New Yorker was an avid defender of Old Glory. After war was declared, business leaders, including many powerful Democrats, pledged funds and goods to the effort. The Irish community, not previously sympathetic to Republicans, vigorously mobilized its own battalion in the first wave of responses to Lincoln’s call for troops to crush the Rebellion. But after the Confederate victory at Bull Run, the wheel turned again. From July 1861 onward for more than a year, the news was unremittingly bad. Battlefield mishaps, crippling inflation, profiteering among war contractors, corruption in the supply of “shoddy” equipment and clothing for the troops, the ability of Confederate raiders to seize dozens of New York merchant ships right outside the harbor, the imposition of an income tax and a controversial effort to reform banking, alarming New York’s regulation-wary financial institutions: all these led to relentless press and public criticism of Lincoln. New York’s cartoonists, as shown in the exhibition, found every possible way to caricature the President’s homely appearance and controversial policies. Even abolitionists and blacks despaired of the President’s reluctance to embrace emancipation and the recruitment of African-Americans into the Union war effort. Former allies such as Horace Greeley slammed Lincoln for putting reunification above freedom as a war goal.

In this gallery, the objects that tell the story will include colorful recruitment posters for the Union army, the great, seldom-lent Thomas Nast painting of the departure of the 7th Regiment for the Front, rare original photographs of the great rally in Union Square on April 21, 1861, and the bullet-shattered coat of Lincoln’s young New York-born friend, and onetime bodyguard, Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, the first Union officer killed in the war.

Gallery 3, titled Bad Blood

(1862), illustrates the mutual animosity of New York’s pro- and anti-Lincoln forces by exhibiting bigger-than-life, three-dimensional versions of the era’s political cartoons. On one side are the Democratic Party politicians and their backers, caricatured by their opponents as bartenders in a political clubhouse, “dispensing a poisonous brew of sedition and fear.” On the other side, a caricature of Lincoln’s New York supporters—officials of the United States Sanitary Commission—shows them enjoying a sumptuous feast, celebrating the ethic of economic opportunity for the rich and the values of hard work, obedience, and self-discipline for the poor. Visitors will see how a powerful New York party of Peace Democrats, or Copperheads, portrayed Lincoln as a despot, warned against “race mongrelization,” and encouraged desertion and draft-dodging. At the same time, the gallery will show how some New Yorkers reaped the benefits of the war, given that their city was the principal home of many of the industries and services Lincoln needed: munitions, shipbuilding, medical supplies, food supplies, money lending and more. Interactive media in Gallery 3 will help visitors (especially of school age) explore the economic issues that so bitterly divided New York.

Gallery 4, Battleground (1862—1864), re-creates seven different conflicts in the city between 1862 and 1864. In each one, the visitor is invited to choose a side, listen to “the talk of the town,” and locate historic landmarks that survive from this era. Among the political and social flashpoints were Lincoln’s issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation- the suspension of habeas corpus and press freedom- the institution of a military draft- the promotion (by Lincoln’s elite Protestant supporters) of a new ethic of civic philanthropy, industrial progress, and national expansion- and the bitter Presidential campaign of 1864. Visitors will be brought into the setting of Shiloh Presbyterian Church (on the corner of Prince and Lafayette Street) on “Jubilee Day,” January 1, 1863, when emancipation was proclaimed- re-live the four-day Manhattan insurrection of July 1863 known as the Draft Riots, which claimed more than 120 lives before they were put down by troops from the 7th Regiment, recalled from Gettysburg- glimpse the crowded pavilions of the loyalists’ Metropolitan Sanitary Fair of April 1864- and see a multitude of cartoons, engravings, pamphlets, flags, posters, lanterns, and campaign memorabilia.

The evolution of Lincoln’s image—from Railsplitter to Jokester to Tyrant to Gentle Father—is the subject of Gallery 5, Eyes on Lincoln. Four iconic portraits, all enormously influential, mostly from life, and none ever displayed together in such a suite—one by Thomas Hicks, one by William Marshall, and two by Francis Bicknell Carpenter (of Lincoln alone and of the assembled family)—anchor the investigation. Interactive programs allow visitors to learn more about the creation and re-production of these images, their iconographic roots in western art, and the artists’ biographies.

The last major gallery, The Loss of a Great Man (1865), takes the visitor from Lincoln’s victory in the 1864 election to his New York funeral procession, perhaps the largest such event yet held in world history, involving hundreds of thousands of participants and inspiring an outburst of mourning among whites and blacks, Christians and Jews, that signaled the transfiguration of the late president’s heretofore-controversial image. A video documents the triumphant events of March and April 1865: the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery, the delivery of the second inaugural address, and the surrender of the Confederate armies. In New York, a gigantic parade celebrated Lincoln on March 5, 1865. And then, after Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, the fierce political antagonisms surrounding Lincoln suddenly evaporated, and a new image emerged of a Christ-like, compassionate, and brooding hero who gave his life so that the nation would enjoy a “new birth of freedom.”

A superb collection of memorial material produced and distributed in the city is accompanied by artwork representing Lincoln’s apotheosis. Included will be the recently discovered scrapbook of a New Yorker who roamed the streets after Lincoln’s death sketching the impromptu written and visual tributes that sprung up in shop windows and on building facades in the wake of Lincoln’s murder. Perhaps the greatest memorial of all was New Yorker Walt Whitman’s poem “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.”

As a coda, the exhibition concludes with a brief tour of how New Yorkers have continued to memorialize Lincoln—in the names of streets and institutions- in the development of an egalitarian national creed- in a powerful sense of nationhood- and in a constantly evolving sense that this is the most representative and inspiring of all Americans.

Catalogue

The exhibition will be accompanied by an illustrated, full-color catalogue edited by guest historian Harold Holzer, who has also contributed an introductory essay and a chapter on the city’s publishers and the making of Lincoln’s image in New York. Additional essays have been written by historians Jean Harvey Baker, Catherine Clinton, James Horton, Michael Kammen, Barnet Schechter, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams, with a preface by New-York Historical Society President and CEO Louise Mirrer, all featuring seldom-seen pictures, artifacts, and documents from the Society collections.

Support for Lincoln and New York

Objects in the exhibition come from the New-York Historical Society’s own rich and extensive collections- from the Gilder Lehrman Collection, on deposit at the New-York Historical Society- Brooks Brothers- and from other major institutions including the Library of Congress, The Cooper Union, Chicago History Museum, John Hay Library at Brown University, Union League Club, New York Military Museum, Cornell University, the University of Illinois, and the New York Public Library.

In addition to generous funding from JPMorgan Chase & Co., the U.S. Department of Education Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural (URR) Program, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, additional project support for the exhibition and related programs has been provided by The Bodman Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, the Motorola Foundation, Brooks Brothers, Con Edison, and the New York Council for the Humanities. Thirteen, a WNET.ORG station, is media sponsor.

About the New-York Historical Society

Established in 1804, the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS) comprises New York’s oldest museum and a nationally renowned research library. N-YHS collects, preserves, and interprets American history and art. Its mission is to make these collections accessible to the broadest public and increase understanding of American history through exhibitions, public programs, and research that reveal the dynamism of history and its impact on the world today. N-YHS holdings cover four centuries of American history and comprise one of the world’s greatest collections of historical artifacts, American art, and other materials documenting the history of the United States as seen through the prism of New York City and State.

Photo: Print by Currier and Ives “The Rail Candidate, 1860″- Lithograph. New-York Historical Society.

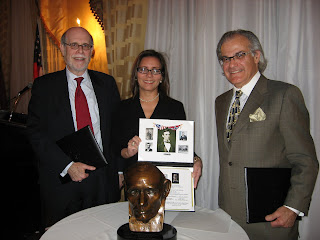

The 2009 Barondess/Lincoln Award was presented at the Round Table’s 537st meeting by Len Rehner, Past President of the CWRT of New York and Chairman of the Awards Committee, and Charles Mander, Current President. Accepting the award for the The New-York Historical Society were three recipients: Dr. Louise Mirrer, President and Chief Executive Officer- Harold Holzer, Chief Historian- and Richard Rabinowitz, Chief Curator for the Exhibit.

The 2009 Barondess/Lincoln Award was presented at the Round Table’s 537st meeting by Len Rehner, Past President of the CWRT of New York and Chairman of the Awards Committee, and Charles Mander, Current President. Accepting the award for the The New-York Historical Society were three recipients: Dr. Louise Mirrer, President and Chief Executive Officer- Harold Holzer, Chief Historian- and Richard Rabinowitz, Chief Curator for the Exhibit.