Among the rock-star personas of the Roaring Twenties were a number of aviators who captured the public’s imagination. Some were as popular and beloved as movie stars and famous athletes, and America followed their every move. It was a time of “firsts” in the world of aviation, led by names like Lindbergh, Byrd, and Post. Among their number was an unusually humble man, Floyd Bennett. He may have been the best of the lot.

Among the rock-star personas of the Roaring Twenties were a number of aviators who captured the public’s imagination. Some were as popular and beloved as movie stars and famous athletes, and America followed their every move. It was a time of “firsts” in the world of aviation, led by names like Lindbergh, Byrd, and Post. Among their number was an unusually humble man, Floyd Bennett. He may have been the best of the lot.

A North Country native and legendary pilot, Bennett has been claimed at times by three different villages as their own. He was born in October 1890 at the southern tip of Lake George in Caldwell (which today is Lake George village). Most of his youth was spent living on the farm of his aunt and uncle in Warrensburg. He also worked for three years in Ticonderoga, where he made many friends. Throughout his life, Floyd maintained ties to all three villages.

In the early 1900s, cars and gasoline-powered engines represented the latest technology. Floyd’s strong interest led him to automobile school, after which he toiled as a mechanic in Ticonderoga for three years. When the United States entered World War I, Bennett, 27, enlisted in the Navy.

While becoming an aviation mechanic, Floyd discovered his aptitude for the pilot’s seat. He attended flight school in Pensacola, Florida, where one of his classmates was Richard E. Byrd, future legendary explorer. For several years, Bennett refined his flying skills, and in 1925, he was selected for duty in Greenland under Lieutenant Byrd.

Fraught with danger and the unknown, the mission sought to learn more about the vast unexplored area of the Arctic Circle. Bennett’s knowledge and hard work were critical to the success of the mission, and, as Byrd would later confirm, the pair almost certainly would have died but for Bennett’s bravery in a moment of crisis.

While flying over extremely rough territory, the plane’s oil gauge suddenly climbed. Had the pressure risen unchecked, an explosion was almost certain. Byrd looked at Bennett, seeking a course of action, and both then turned their attention to the terrain below.

Within seconds, reality set in—there was no possibility of landing. With that, Bennett climbed out onto the plane’s wing in frigid conditions and loosened the oil cap, relieving the pressure. He suffered frostbite in the process, but left no doubt in Byrd’s mind that, in selecting Bennett, he had made the right choice.

The two men became fast friends, and when the intrepid Byrd planned a historic flight to the North Pole, Bennett was asked to serve as both pilot and mechanic on the Josephine Ford. (Edsel Ford provided financial backing for the effort, and the plane was named after his daughter.) In 1926, Byrd and Bennett attained legendary status by completing the mission despite bad luck and perilous conditions. The flight rocketed them to superstardom.

Lauded as national heroes, they were suddenly in great demand, beginning with a tickertape parade in New York City. Byrd enjoyed the limelight, but also heaped praise on the unassuming Bennett, assuring all that the attempt would never have been made without his trusted partner. When Bennett visited Lake George, more than two thousand supporters gathered in the tiny village to welcome him. As part of the ceremony, letters of praise from Governor Smith and President Coolidge were read to the crowd.

Both men were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest award for any member of the armed services, and rarely bestowed for non-military accomplishments. They were also honored with gold medals from the National Geographic Society. Despite all the attention and lavish praise, Bennett remained unchanged, to the surprise of no one.

Both men were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest award for any member of the armed services, and rarely bestowed for non-military accomplishments. They were also honored with gold medals from the National Geographic Society. Despite all the attention and lavish praise, Bennett remained unchanged, to the surprise of no one.

The next challenge for the team of Bennett and Byrd was the first transatlantic flight from New York to Paris, a trip they prepared for eagerly. But in a training crash, both men were hurt. Bennett’s injuries were serious, and before the pair could recover and continue the pursuit of their goal, Charles Lindbergh accomplished the historic feat. Once healed, the duo completed the flight to Europe six weeks later.

Seeking new horizons to conquer, aviation’s most famous team planned an expedition to the South Pole. Tremendous preparation was required, including testing of innovative equipment. On March 13, 1928, a curious crowd gathered on the shores of Lake Champlain near Ticonderoga. Airplanes were still a novelty then, and two craft were seen circling overhead. Finally, one of them put down on the slushy, ice-covered lake surface, skiing to a halt.

Out came local hero Floyd Bennett, quickly engulfed by a crowd of friends and well-wishers. While in Staten Island preparing for the South Pole flight, he needed to test new skis for landing capabilities in the snow. What better place to do it than among friends? After performing several test landings on Lake Champlain, Bennett stayed overnight in Ticonderoga. Whether at the Elks Club, a restaurant, or a local hotel, he and his companions were invariably treated like royalty. Bennett repeatedly expressed his thanks and appreciation for such a warm welcome.

A month later, while making further preparations for the next adventure, Floyd became ill with what was believed to be a cold. When word arrived that help was urgently needed on a rescue mission, the response was predictable. Ignoring his own health, Bennett immediately went to the assistance of a German and Irish team that had crossed the Atlantic but crashed their craft, the Bremen, on Greenly Island north of Newfoundland, Canada.

During the mission, Floyd developed a high fever but still tried to continue the rescue effort. His condition worsened, requiring hospitalization in Quebec City, where doctors found he was gravely ill with pneumonia. Richard Byrd and Floyd’s wife, Cora, who was also ill, flew north to be with him. Despite the best efforts of physicians, Bennett, just 38 years old, succumbed on April 25, 1928, barely a month after his uplifting visit to Ticonderoga.

Though Bennett died, the rescue mission he had begun proved successful. Across Canada, Germany, Ireland, and the United States, headlines mourned the loss of a hero who had given his life while trying to save others. Explorers, adventurers, and aviators praised Bennett as a man of grace, intelligence, bravery, and unfailing integrity.

Floyd Bennett was already considered a hero long before the rescue attempt. The selflessness he displayed further enhanced his image, and as the nation mourned, his greatness was honored with a heavily attended military funeral in Washington, followed by burial in Arlington National Cemetery. Among the pile of wreaths on his grave was one from President and Mrs. Coolidge.

After the loss of his partner and best friend, Richard Byrd’s craft for the ultimately successful flight to the South Pole was a tri-motor Ford renamed the Floyd Bennett. Both the man and the plane of the same name are an important part of American aviation history.

It was e ventually calculated th

ventually calculated th

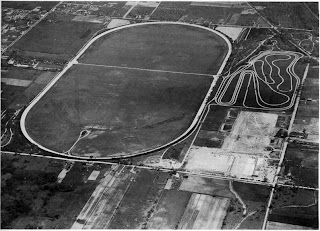

at the earlier flight to the North Pole may not have reached its destination, but the news did nothing to diminish Byrd and Bennett’s achievements. They received many honors for their spectacular adventures. On June 26, 1930, a dedication ceremony was held in Brooklyn for New York City’s first-ever municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field. It was regarded at the time as America’s finest airfield.

Many historic flights originated or ended at Floyd Bennett Field, including trips by such notables as Howard Hughes, Jimmy Doolittle, Wiley Post, Douglas “Wrongway” Corrigan, and Amelia Earhart. It was also the busiest airfield in the United States during World War II, vital to the Allied victory. Floyd Bennett Field is now protected by the National Park Service as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

The beloved Bennett was also honored in several other venues. In the 1940s, a Navy Destroyer, the USS Bennett, was named in honor of his legacy as a flight pioneer. In the village of Warrensburg, New York, a memorial bandstand was erected in Bennett’s honor. Sixteen miles southeast of Warrensburg, and a few miles from Glens Falls, is Floyd Bennett Memorial Airport.

In a speech made after the North Pole flight, Richard Byrd said, “I would rather have had Floyd Bennett with me than any man I know of.” High praise indeed between heroes and friends. And not bad for a regular guy from Lake George, Warrensburg, and Ticonderoga.

Top Photo: The Josephine Ford.

Middle Photo: Floyd Bennett, right, receives medal from President Coolidge. Richard Byrd is to the President’s left.

Bottom Photo: Floyd Bennett Field, New York City’s first municipal airport.

Lawrence Gooley has authored ten books and dozens of articles on the North Country’s past. He and his partner, Jill McKee, founded Bloated Toe Enterprises in 2004. Expanding their services in 2008, they have produced 19 titles to date, and are now offering web design. For information on book publishing, visit Bloated Toe Publishing.

Columbia University Press has announced the publication of The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011, edited by Hilary Ballon, which includes more than 150 illustrations and a gatefold of the original plan. The book accompanies the exhibit of the same name which just opened at the Museum of the City of New York.

Columbia University Press has announced the publication of The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011, edited by Hilary Ballon, which includes more than 150 illustrations and a gatefold of the original plan. The book accompanies the exhibit of the same name which just opened at the Museum of the City of New York.