One of the problems in researching the life of Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck is that there are so few primary sources written by him left to us. We are fortunate that at least one of the treasures that give us a peek into his life, one of his account ledgers, has been preserved. It is a rich source for a researcher of not only Hasbrouck, but of others from his time period as well.

One of the problems in researching the life of Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck is that there are so few primary sources written by him left to us. We are fortunate that at least one of the treasures that give us a peek into his life, one of his account ledgers, has been preserved. It is a rich source for a researcher of not only Hasbrouck, but of others from his time period as well.

Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck was born in 1722 in Ulster County just outside of New Paltz, New York. He later relocated in 1749 to what would become Newburgh, where his mother Elsie Schoonmaker purchased 99 acres of land.

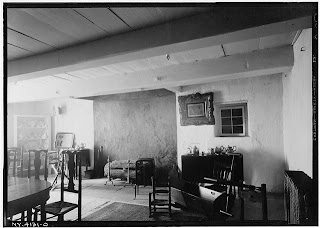

These 99 acres would form the heart of his farm, mills, and merchant activity, which he would expand for the rest of his life. His home was also enlarged until it took its present form by 1770. He brought his wife Tryntje to the home in June 1751 after they were married. The couple had several children named: Mary, Rachel, Joseph, Abraham, Cornelius, Jonathan, and Isaac. Joseph and Abraham would both pass away in the 1770s.

Hasbrouck’s ledger gives us a great peak into the preparations made for the defense of the Hudson and also reveals names of the various participants in that struggle. If we take a look at some of the specific entries within the first few pages, we find that supplies are received by Hasbrouck for powder and lead to be used in the “defense of the states.” Some of these deliveries were also parceled out to his officers. Another entry reads that Captain Conklin was given a “French Musket,” which can tell us what types of weapons the militia had access to around Newburgh in 1776.

Additionally, the document tells historians where Hasbrouck was stationed, and who he was stationed with. An example of this was Fort Montgomery, which was located on the Hudson. Hasbrouck, along with other members of the militia helped in its construction and protection. It was hoped that the fort, along with Fort Clinton and the first chain across the Hudson, would play a vital role in the defense of the Hudson and would prevent British excursions up the river.

An entry dated June 20th, 1777 reveals that Hasbrouck was stationed with Lt. McNeals’ company. About four months later, Fort Montgomery would be attacked by the British and would fall. The British would then make their way up the Hudson River ultimately burning Kingston, the state capital.

Hasbrouck was not present at the battle of Fort Montgomery, as he was convalescing in his home. He speaks about this in a letter to Brigadier General George Clinton. Prior to the fall of Fort Montgomery, a significant part of Hasbrouck’s ledger pertains to the time in which he was stationed there. Many of his entries during this time were for payments to various officers and soldiers for their services.

In addition, there are other interesting notes pertaining to his profession as a merchant, miller, and store owner. For example, an entry of “three hundred dollars” for “1900 pounds of tobacco” was recorded, which revealed the importance of this commodity not only for everyday use, but for soldiers as well. Quite possibly, while Hasbrouck was recovering from an illness in 1777, his son Cornelius Hasbrouck picked up the business slack by transporting, amongst other things, clothing. In the spring of 1779, Hasbrouck was transacting again – he carted “8 hogs heads of rum” and took in “1600 dollars” for them which he shared with a Joseph Gashire. Much of the entries pertaining to 1779 deal directly with the fortune that the Hasbrouck family was making as merchants in Newburgh and include references to flour, hops and other commodities.

What I personally find interesting are entries relating to his son Cornelius. One entry states that Hasbrouck received Continental or U.S. Government cattle. These cattle were kept, according to papers in the New York State Archives, in his upper meadow as well as around his mill. Hasbrouck was paid for keeping these cattle, the same cattle that are later a source of trouble for Cornelius, as he decides to steal some. It turns out that a “bullock” which Cornelius took had an “NH” on his horn- this type of bullock is referenced in the ledger. Later depositions reveal that there are cattle sold that have the brand “NH” on their horns.

Later entries, especially those made by family members after Hasbrouck dies, pertain to the lands that the Hasbroucks owned in and around Newburgh. They are for various taxes to be paid on their lands in New Windsor and Newburgh. These taxes range from poor taxes to county taxes. After Hasbrouck’s death in the summer of 1780, his wife Tryntje continued to pay these various taxes even when it was obvious that General Washington was occupying their home as his headquarters. Tryntje’s exact whereabouts during this time aren’t known for sure. What is telling is that an entry reads “received Newburgh”, possibly indicating that even as Washington lived in her home, she might have been in the area. Many earlier historians believe, however, that Tryntje relocated to New Paltz.

The account ledger, which is on file at Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site in Newburgh, New York, encompasses the years 1776 to the late 1780s. It covers the period when Colonel Hasbrouck was active as a militia colonel in 1776, through his resignation of that commission permanently in 1778, and finally to his death in 1780. After he died, his ledger was clearly taken over by his widow Tryntje and later by his sons, most notably Jonathan Hasbrouck, Jr.

A unique aspect of the ledger which deserves some attention is that it appears a family member saw a few blank pages in this old ledger and started keeping recipes in the back. It cannot be definitively proven who this person actually was or if it even was a Hasbrouck. They are interesting for delving into the Hasbrouck’s culinary tastes- if, once again, they are actually Hasbrouck family recipes.

The recipe for Washington Cake stands out as more or less the same recipe for Martha Washington’s Great Cake, which was one of George Washington’s favorites. There was a recipe for ice cream, which had been around since the time of Washington and was even served by Jefferson – both presidents had ice houses. Also contained in the ledger were recipes for macaroons, apple tarts, and puff pastries. The author of these recipes is not recorded.

The ledger of Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck should not be overlooked, as it provides a glance into the life of a prominent family and also offers information pertaining to the American War for Independence in the Lower Hudson Valley. It is also a rich resource for genealogists hoping to trace various individuals and their corresponding places during specific times in the conflict. Perhaps one day another ledger will be found that was kept by Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck, but until then, this is a great source.

Photo courtesy HABS/HAER Library of Congress.