On May 12, 1903, Franklin County attorney Robert M. Moore was at wit’s end. After two years of haggling, all possibilities had been exhausted, and he knew his client was in serious trouble. There was nothing left but a claim of insanity. If that failed, a man was sure to die.

On May 12, 1903, Franklin County attorney Robert M. Moore was at wit’s end. After two years of haggling, all possibilities had been exhausted, and he knew his client was in serious trouble. There was nothing left but a claim of insanity. If that failed, a man was sure to die.

The client was Allen Mooney, and his crime in Saranac Lake became one of the most talked-about murders in North Country lore. It’s not a particularly complex tale, but its salacious and violent aspects guaranteed plenty of media coverage. Legally, it was pretty much a cut-and-dried case. Mooney admitted the shootings, and there was plenty of evidence against him.

However, peripheral factors never mentioned in testimony may have “eased” the jury’s decision. And, there were opinions voiced in court that would never be allowed to reach a modern jury’s ears. It all combined to determine a man’s fate. Not to say that Mooney would have otherwise been found innocent- he was guilty, but his sentence may have differed sharply.

In the early 1900s, Saranac Lake was in some ways like the Wild West. Smuggling, shootings, public drunkenness, prostitution, and murder were subjects bemoaned in the press as far too frequent. Any day was a good day for hell-raising, but Election Day was a particular favorite in many towns. Of course, the folks involved in Mooney’s crime led pretty rough lives. They may well have been clueless that it was Election Day.

The year was 1902, and the principals were: Allen Mooney, 25, a plumber’s assistant- Fred McClelland, 30, a friend of Mooney’s- Charles Merrill, 22, a local laborer and Mooney’s nephew- Viola Middleton, about 30, housemate of McClelland- and Ellen Thomas, about 24, known in Saranac Lake as Ethel “Maude” Faysette, love interest of both Mooney and Merrill.

On Election Day, the group was said to have been drinking and carousing at McClelland’s house. When Mooney eventually became loud and abusive, Fred threw him out. Testimony about the day’s events varied, but there was no disagreement on what happened that evening. Mooney, fueled with alcohol and driven by jealousy over Ellen Thomas, managed to get into the house through a door that had only a chair propped against it (the lock didn’t work properly).

By all accounts, he entered a bedroom and found McClelland there with Middleton. Mooney aimed his gun at McClelland, telling him “If you have anything to say, then say it quick.” After a momentary pause, Mooney fired two shots. One hit McClelland and deflected into Viola Middleton, and the other struck Middleton directly.

By all accounts, he entered a bedroom and found McClelland there with Middleton. Mooney aimed his gun at McClelland, telling him “If you have anything to say, then say it quick.” After a momentary pause, Mooney fired two shots. One hit McClelland and deflected into Viola Middleton, and the other struck Middleton directly.

Charles Merrill and Ellen Thomas were in another room together. When the shooting began, Merrill hid beneath the bed. Mooney entered, shot the girl twice, and left the room. Charles Merrill was uninjured, and most reports claim he managed to jump Mooney, subdue him, secure the gun, and hold him until a local officer arrived.

Both men were jailed (Merrill as a witness), and Mooney was said to have soon fallen into a deep sleep. Upon waking the next morning, he claimed to have no recollection of the previous night’s events.

McClelland’s wounds were serious, but he survived. Ellen Thomas died shortly after the shooting, and Viola Middleton lasted only a few days. In spring 1903, Mooney was indicted on two counts of first-degree murder and one count of assault. Awaiting trial, he was held on the bottom floor of the county jail in Malone, in what was referred to as “the cage.”

As usual, the case was tried in the newspapers until the actual trial date arrived. There were stories of Ellen Thomas (as Maude Faysette) having been arrested two days before the shooting, only to be released the next day. And, local bars were taken to task over serving liquor to Allen Mooney, knowing his condition and his reputation.

In May 1903, court testimony confirmed the shooting was done by Mooney in a drunken, jealous rage. Intent was proven by his purchase of a gun and cartridges that afternoon. Upon arrest, he reportedly said words to the effect, “I’ll go quietly. I’ve made a fool of myself.” Attorney Moore, left with no other defense, hoped to prove Mooney’s insanity at the time of the shooting.

As evidence, he cited Mooney’s aunt (his father’s sister), who “lost all control of herself” during hysterical fits that kept her confined in a Canadian asylum for many years. And Mooney himself was said to have suffered epileptic seizures since childhood, often turning violent during the attacks. Doctors said that due to his physical condition, a small amount of alcohol could cause him to “become violently insane and unconscious of his acts.”

Most interesting of all were the professional opinions about Mooney’s appearance. As one reporter wrote, the doctors said, “From the peculiarities of his head, eyes, and looks, they would classify him as a degenerate who was more susceptible to insanity than a normal man.” Add the booze, and you had a powder keg, but one that was not responsible for its own explosion.

The prosecution was inclined to agree?partially. Four doctors, including one from the St. Lawrence State Hospital (informally known as the Ogdensburg Insane Asylum), upped the ante with this assessment: Mooney “… represented a low type of manhood and possessed certain peculiarities of degeneracy.” But they also felt he was rational, and based on the same factors cited by the defense—physical condition, appearance, and actions—they believed Mooney was conscious of his acts.

Next week: The verdict- some interesting new friends- Mooney’s introduction to the famous (or infamous) Robert Elliott.

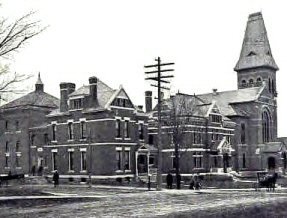

Photos: The Franklin County Government Buildings, early 1900s- Saranac Lake in the early 1900s.