Despite the physical evidence against Saranac’s Allen Mooney in the murders of Ellen Thomas and Viola Middleton, he could still hope for a lesser conviction, even manslaughter, due to extenuating circumstances. Epilepsy, a weakness for drink, extreme jealousy—the man was obviously beset by many problems. Not a saint by any stretch, but was he a wanton killer?

Despite the physical evidence against Saranac’s Allen Mooney in the murders of Ellen Thomas and Viola Middleton, he could still hope for a lesser conviction, even manslaughter, due to extenuating circumstances. Epilepsy, a weakness for drink, extreme jealousy—the man was obviously beset by many problems. Not a saint by any stretch, but was he a wanton killer?

Unspoken, though, was another factor—Mooney’s extended family. His relatives from the Malone area, and south to Saranac Lake—the Merrills, Jocks, Stacys, and other Mooneys—shared quite the infamous reputation. In the decade surrounding Mooney’s trial, this motley group committed assaults, burglaries, robberies, wife beatings, at least 3 murders (and a fourth suspected with arson), prostitution, incest, child abuse, family abandonment, and more.

This was no secret. Leading up to the trial, many of the family’s escapades had been highly publicized in recent years. It would be very difficult for jurors to ignore that reality. And, if Mooney should be considered insane because his aunt was insane (as the defense claimed), then maybe he was an incorrigible criminal like so many members of his extended family.

The courtroom was packed throughout the trial, and extensive testimony hinted that the jury might struggle to reach a verdict. During deliberations, the first vote was 7 for first-degree murder and 5 for second-degree murder. With that much uncertainty, a consensus seemed unlikely. It appeared Mooney might be spending the rest of his life behind bars, but at least he’d be alive.

Early the next morning, though, almost before the court session began, it was suddenly over. The verdict was in: guilty of murder in the first degree. Mooney was told to stand, and the judge pronounced sentence: “That you be confined in Dannemora State Prison until the week beginning July 6, 1903, when, in compliance with the law, you shall suffer death by having a current of electricity pass through your body until you are pronounced dead.” Mooney, calm as ever, spoke only to thank the judge.

He was a condemned man with just six weeks left to live, but Mooney wasn’t the only one under pressure. Dannemora’s executioner felt a little heat as well. He was scheduled to dispose of six prisoners during the week of July 6, including a widely infamous threesome, the Van Wormer brothers, who had brutally murdered their uncle and terrorized his family.

Joining them were William “Goat Hinch” O’Conner (committed murder during a robbery), and Kate Taylor, who was believed long abused by her husband (until she killed him, cut off his head, stuck it in an oven, tried to cut off his leg, burned the corpse, and fed the bones and ashes to the chickens). Allen Mooney was in fine company.

Appeals delayed his execution (and Taylor’s, too), subjecting Mooney to unexpected angst. Taylor, female, was held in a special cell, but Allen was with the others on Death Row. Described during his trial as “stolidly indifferent,” Mooney now sat nearby as, one by one, the Van Wormers were walked down the hallway to waiting death. Each said goodbye to Mooney.

Appeals delayed his execution (and Taylor’s, too), subjecting Mooney to unexpected angst. Taylor, female, was held in a special cell, but Allen was with the others on Death Row. Described during his trial as “stolidly indifferent,” Mooney now sat nearby as, one by one, the Van Wormers were walked down the hallway to waiting death. Each said goodbye to Mooney.

Reports of the boys’ final moments appeared beneath large, bold headlines in newspapers across the country. The last to go was the middle brother, and in memorable fashion:

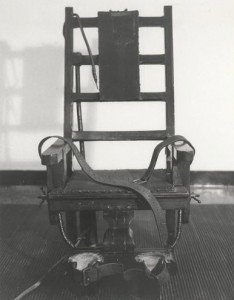

“Burton’s departure from the death house made the most pathetic scene of all. Besides the aged priest, there was but one person in the world to whom he might say goodbye. That was Allen Mooney, the last occupant of the death cells, who sat in the corner of the front of his cell, sobbing like a child. As Burton stepped from his cell, he looked back toward Mooney’s cell, which was out of his view because of a great iron screen built for that purpose, and called: ‘Goodbye Mooney. I hope you don’t have to go like this.’ And then he marched to the death chair.”

The procession of priest, warden, and guards guided Van Wormer to the death room, where, for the first and last time, he met Robert Elliott, Dannemora’s chief executioner.

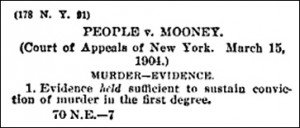

Mooney’s reprieve lasted five months, when the court of appeals affirmed his sentence. The execution was two months away, but within a month, reports surfaced that he wasn’t eating, and mostly languished in his cell, deteriorating physically. But after watching the Van Wormers, who converted to Catholicism and carried crucifixes as they went to their deaths, Mooney took action. He summoned the Catholic priest and converted from the Baptist faith he had been born into (but apparently ignored), hurrying to achieve baptism and first communion by March.

Mooney’s reprieve lasted five months, when the court of appeals affirmed his sentence. The execution was two months away, but within a month, reports surfaced that he wasn’t eating, and mostly languished in his cell, deteriorating physically. But after watching the Van Wormers, who converted to Catholicism and carried crucifixes as they went to their deaths, Mooney took action. He summoned the Catholic priest and converted from the Baptist faith he had been born into (but apparently ignored), hurrying to achieve baptism and first communion by March.

Two months later, just as his cellmates had done, Mooney took Communion and clung tightly to a crucifix. On May 3, 1904, he walked his final steps to join Robert Elliott and the waiting chair. One electrode was attached to his head, and less than four minutes later, Mooney was gone.

To the relief of some, a subsequent autopsy revealed that his liver and kidneys were in good condition, dispelling the notion that physical infirmities in Mooney’s organs might have caused momentary insanity. He was the only inmate executed at the prison in 1904, and the only Franklin County resident to die in Dannemora’s electric chair.

Photos: Saranac Lake early street view- Court of Appeals document upholding Mooney’s conviction– Sing Sing’s electric chair, same as the one in which Mooney died.