It is hard to imagine now but in the 18th century New York City and much of the rest of the thirteen British colonies of America, it was practically illegal to be a Roman Catholic. Widespread anti-Catholicism was a side effect of the Catholic-Protestant wars of 17th century Europe and the geo-political rivalries between the English Crown and the allied Franco Spanish Kingdoms for control of the Americas.

It is hard to imagine now but in the 18th century New York City and much of the rest of the thirteen British colonies of America, it was practically illegal to be a Roman Catholic. Widespread anti-Catholicism was a side effect of the Catholic-Protestant wars of 17th century Europe and the geo-political rivalries between the English Crown and the allied Franco Spanish Kingdoms for control of the Americas.

The anti-Catholic animosity – Leyenda Negra the Spanish called it – was ingrained into the psyche of the largely Protestant British immigrants who came to dominate North America in the wake of the arrival of the Pilgrims and other fundamentalists in the early 1600s.

Despite the aide that the Catholic kings of France and Spain lent to the Revolution, this hard line persisted well into the 18th century and beyond. It was still quite difficult to be a Catholic in New York (and other States) and the faithful had no proper church to worship in except for clandestine Mass’ at private homes. One of the more prominent of these belonged to the Spanish ambassador to the United States, Don Diego de Guardoqui. He along with his military counterpart, General Bernardo Galvez, were largely responsible for the considerable, but largely forgotten aide the Spain gave toward the liberation of the American colonies from Great Britain.

In 1789 de Guardoqi, a wealthy Portuguese merchant named Jose Ruiz Sliva and French diplomat, Hector St Jean Crevecoeur teamed up to petition New York City’s Mayor and Common Council for permission to have “a suitable site upon which we can construct a church.” Interestingly enough, Crevecoeur was not a Catholic but he was sympathetic to the ideal of religious freedom and a close friend of Revolutionary War hero, the Marquis de Lafayette. Accordingly, De Guardoqui, Ruiz Silva and other Catholic laymen felt that the French diplomat was their best chance for getting site approval. Despite Crevecoeur’s efforts, City officials were not moved and the City’s Catholics sought help from Trinity Church (formerly Anglican and now Episcopalian) which leased property for a Catholic Church at a nominal fee on the corner of what is now Church and Barclay streets, then on the periphery of the city.

The legal founding of St. Peter’s parish dates to June of 1785, when a small group of Catholics, including affluent merchants and diplomats such as de Guardoqui, Crevecoeur, Jose Ruiz Silva, James Steward, and Henry Duffin, declared themselves to be ‘‘The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church in the City of New York.’’ New York law required each religious body to have a board of trustees consisting of representatives of its laity. These trustees, who were defined by the statute as men who would ‘‘take the charge of the estate.” The newly established congregation then turned to their European co-religionists for funds to build the church. They appealed directly to King Carlos III of Spain and King Louis XVI of France for financial support.

Despite Crevecoeur’s efforts, however, the French government offered little monetary assistance. Eventually, His Most Catholic Majesty Carlos III, King of Spain, emerged as the primary sponsor of St. Peter’s when he donated 1000 “Pesos Fuertes” to build the church. Also known as the Spanish dollar and the piece of eight, the “Peso Fuerte” was a silver coin minted in the Spanish Empire that was legal tender in the United States until 1857. Because it was widely used in Europe, the Americas, and the Far East, it became the first world currency by the late 18th century.

Despite Crevecoeur’s efforts, however, the French government offered little monetary assistance. Eventually, His Most Catholic Majesty Carlos III, King of Spain, emerged as the primary sponsor of St. Peter’s when he donated 1000 “Pesos Fuertes” to build the church. Also known as the Spanish dollar and the piece of eight, the “Peso Fuerte” was a silver coin minted in the Spanish Empire that was legal tender in the United States until 1857. Because it was widely used in Europe, the Americas, and the Far East, it became the first world currency by the late 18th century.

New York’s Catholics thanked Charles for the ‘‘attention and friendship’’ that he had shown them and they promised that in honor of his generosity, they would ‘‘take the liberty of erecting a tribune in the most distinguished place and of reserving it for His Majesty’s use’’ in the event that Charles ever visited St. Peter’s. Folklore has it that this promise was fulfilled when several Pesos Fuertes with the likeness of Carlos were placed in the cornerstone of the church by de Guardogui.

The ground breaking for Manhattan’s first Catholic church since the late seventeenth century took place on November 4, 1785, the feast day of St. Carlos Borromeo, for whom King Carlos of Spain had been named. To highlight the Spanish role in funding St. Peter’s, the Spanish packet San Carlos sailed into New York Harbor decorated for the occasion and firing many salutes in honor of the king. New York Catholics gave Don Diego de Gardoqui, the Spanish ambassador to the United States, the honor of laying the cornerstone of the church.

The ground breaking for Manhattan’s first Catholic church since the late seventeenth century took place on November 4, 1785, the feast day of St. Carlos Borromeo, for whom King Carlos of Spain had been named. To highlight the Spanish role in funding St. Peter’s, the Spanish packet San Carlos sailed into New York Harbor decorated for the occasion and firing many salutes in honor of the king. New York Catholics gave Don Diego de Gardoqui, the Spanish ambassador to the United States, the honor of laying the cornerstone of the church.

After the laying of the cornerstone a public Mass was celebrated at de Gardoqui’s residence, following which the Catholic diplomat ‘‘gave a very elegant entertainment to the first personages of this City.’’ A Mexican artist, Jose Vallejo, was commissioned to paint an icon of the Crucifixion, and the archbishop of Mexico City, Nunez de Haro bestowed it upon Saint Peter’s parish. After completion of the church in 1786, it was hung above the main altar.

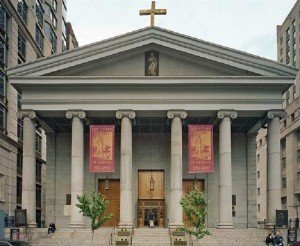

Illustrations: Above, the original St. Peter Church (circa 1785)- middle, a Spanish Silver Dollar with the Image of Carlos III and the Coat of Arms of Spain- below, St Peter’s as it appeared on the occasion of its 225th Anniversary of its founding. This replacement building was constructed in 1834 on the grounds of the original church.