Thomas Cole (1801-1848) , English immigrant, is regarded as a father of the Hudson River School, the first national art expression of the American identity in the post-War of 1812 period. It was a time when we no longer had to look over our shoulder at what England was doing and could begin to think of ourselves as having a manifest destiny. Cole also was very much part of the birth of tourism which occurred in the Hudson Valley and points north and west.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848) , English immigrant, is regarded as a father of the Hudson River School, the first national art expression of the American identity in the post-War of 1812 period. It was a time when we no longer had to look over our shoulder at what England was doing and could begin to think of ourselves as having a manifest destiny. Cole also was very much part of the birth of tourism which occurred in the Hudson Valley and points north and west.

When Cole arrived in America at age 17 with his family, he did not settle in the New York area in which he would become so closely associated. His family peregrinations took him west into the wilderness before he arrived in Philadelphia ready to pursue an art career. At that time, Philadelphia was the “nation’s capital” but it was in the process of losing that title to New York even before the Erie Canal was completed. Cole’s move to New York signaled a transformation already underway as the cultural, financial, sports, and artistic center of the country shifted from the city that dominated at the birth of the country to the one would for centuries to come.

In his first journey north in 1825, he visited and then painted a View of Fort Putnam. The Fort is located on the campus of the United States Military Academy and commands the infamous S-curve on the Hudson River where the “west point” of the shore juts out towards Constitution Island with its own fort on the east side. The decades since Arnold attempted to turn the Fort over to the British had not been kind to the Fort and it had experienced even more decay than under Arnold’s watch. Fort Ticonderoga had experienced a similar decline once its services were no longer required.

Fort Putnam then may be regarded as our first “ruin porn,” a predecessor to the Hudson Valley Ruins which have been chronicled in a book by the same name and of Detroit as written about in previous posts. One of the traditional claims regarding the Hudson River School was that America did not have the ruined cathedrals, aqueducts, palaces, and tombs of Europe that were traditional objects for painters so instead our painters turned towards the works of God not man, the world as He had created it before man had altered it. Cole first painting therefore draws on European tradition of ruins but transplanted to an American context.

Determining exactly what Cole had done proved problematical because the painting disappeared from sight. Future Hudson River School painter Asher Durand purchased it immediately and probably kept it until he died, but then the trail turned cold. By chance it was recovered from a warehouse following a fire in the early 1990s although at first no one knew what it was. Darrel Sewell, then the Robert L. McNeil Jr., curator of American art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, initially identified the painting as an early work by Cole based on the signature and technical quality. This attribution was later endorsed by the art historian and Cole authority Ellwood C. Parry III.

Curator Elise Effmann from the Museum spoke at the Thomas Cole House in 2007 on the restoration of the painting. She said/wrote, “The canvas and paint required stabilization following minor water damage in the warehouse fire. Practically untouched for decades, the landscape was also obscured by discolored varnish and a heavy layer of grime. The painting is now the promised gift of its owner, Charlene Sussel, in honor of the museum’s 125th anniversary.” The before and after curated images truly were a remarkable contrast.

The restoration enables one to see what Cole sought to accomplish with this his first painting. Durand provided his interpretation of the painting in 1830 in the premiere edition of The American Landscape (1830)

It is a feature almost unique in American scenery, reminding the traveler of the romantic ruined towers of defence in the gorges of the Pyrenees, or the feudal castles which still frown from the rocky banks of the Rhine…-. These ruins are rich with the most hallowed associations- for they are fraught with recollections of heroism, liberty, and virtue…-. As we muse over this magnificent scene of great events, the imagination insensibly kindles, and the plain below, and the forts, and rocks, become peopled again with the soldiers and chiefs of the revolution…-. Amid the ruins of Fort Putnam, the patriot may find materials to animate him with fresh hopes for his country’s future welfare, as well as to recall the noblest recollections of her past history.

Immigrant Cole heard this call to the events which had led to creation of his adopted country. He was an American now.

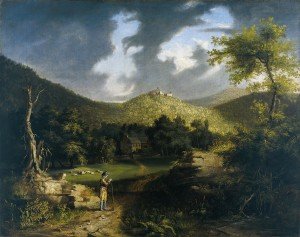

The scene at West Point contains a more overt reference to the Revolutionary War as well. Like a medieval castle, Fort Putnam endows the landscape with a sense of grandeur and history that intentionally rivals the European tradition. This reference is underscored by Cole’s assimilation of the notion of the sublime into the scene, with its vaguely threatening clouds and areas of deep shadow. It was this very mixture of skillful painting, depth of meaning, and acknowledgment of a broader tradition that attracted the eyes of Trumbull, Dunlap, and Durand to the three paintings that launched Cole’s career.

Art historian David Schuyler, in “The Mid-Hudson Valley as Iconic Landscape: Tourism, Economic Development, and the Beginning of a Preservationist Impulse,” observed:

West Point was the American shrine, the sacred place where American independence hung in precarious balance during the dark days of the Revolution

So long before Ground Zero became the cosmic center where the forces of darkness confronted the forces of light, long before the dark cloud of the smoke monster smothered the city like an alien presence, long before the light of Lady Liberty illuminated the heavens, long before the blue beam of hope boldly shone where once the World Trade Towers had stood, Fort Putnam stood as the place where at the dawn of the this country the showdown between good and evil, between Washington and Arnold occurred. While in real life both were human beings, Cole correctly realized that both had become avatars, exemplars, symbols, of two contrasting ways of life. The painting pictures a young man about to embark on his journey in life under the watchful protection of the ruined fort that represented where good had triumphed over evil at the showdown in America’s first cosmic center.

From Fort Putnam, Cole continued north in his paintings eventually making Catskill his home and becoming a defining voice in the Jacksonian Era which ended with the administration of Columbia County’s Van Buren. There are so many Paths through History which could be created out of these formative events in New York and American history it is shame that not one of them will be.

Illustration: Thomas Cole’s View of Fort Putnam (1825).

Hi Peter I was at Fort Putnam last summer and it is in pretty good shape. The Fort is under the supervision of the West Point Museum Director, David M. Reel and if you contact him he can arrange access.