FBI agents described Ticonderoga’s Bernard Frederick Champagne as “a prolific impersonator,” but the true extent of his success is unknown. Because so much of his fakery escaped detection, it’s unclear how many identities Bernard actually assumed. One agent said he had “at least 50 aliases,” and at one point, there were 34 names documented. It was the list of professions, however, that really impressed them.

FBI agents described Ticonderoga’s Bernard Frederick Champagne as “a prolific impersonator,” but the true extent of his success is unknown. Because so much of his fakery escaped detection, it’s unclear how many identities Bernard actually assumed. One agent said he had “at least 50 aliases,” and at one point, there were 34 names documented. It was the list of professions, however, that really impressed them.

Among his successful impersonations were: a graduate of Columbia University- a doctor employed by the US Public Health Service- a secret service agent- an FBI agent- a member of the US diplomatic corps- and the nephew of noted politician Hamilton Fish, a ruse that allowed him to pass $600 worth of bogus checks ($8,300 in 2013).

On a grander scale were his military personas: an army medical officer- aide to General Arnold, who was chief of the nation’s air forces- a member of military intelligence- a lieutenant colonel in the army (good for another $8,000 in 2013)- a lieutenant commander in the US Navy- and a nephew of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was commanding the Allied forces in Europe.

At times he claimed to have lost three brothers in the Battle of the Coral Sea- that his brother-in-law was an admiral- and that his grandfather was a navy captain. Those lies, offered convincingly, gave him legitimacy in the eyes of an intended victim. It was an important factor leading up to the payoff scheme: ensuring that he could secure the release of relatives in Germany. By carefully selecting his marks (victims), Bernard achieved continued success.

An FBI memo from summer 1943 notes that Champagne’s proclivity for “victimizing women, especially widows” was featured in a radio broadcast by the legendary Walter Winchell. Hoover, passionate guardian of the FBI’s reputation, felt that publicly citing a longstanding, unsolved case made the Bureau look bad. It was his baby, and he felt the need to respond.

The same memo confirmed that increased attention was now focused on Bernard: “An identification order was issued on Champagne during the past week, and a very active fugitive investigation looking to his apprehension is in progress.”

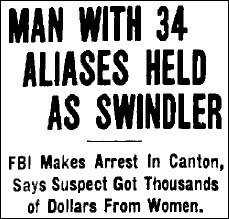

Less than two months later, Hoover had his man. Bernard’s modus operandus was well known, and information detailing it was disseminated to scores of law enforcement agencies. Anything remotely resembling his style was looked at, and a case in Ohio proved his undoing.

In the small village of Dalton, Bernard had targeted a widow, Gladys Mohn, in a real estate scheme. Presenting himself as Allen Steven Klein, a navy surgeon, he convinced Mrs. Mohn to invest $4,312 ($56,000 in 2013) in some Florida property, land that he said the government was going to purchase for airport development. The return promised by Champagne on her investment was $22,000 ($286,000 in 2013).

A glitch developed when Mohn went to Florida with Champagne to look the site over. After several excuses “prevented” him from showing her the property, which of course didn’t exist, Bernard finally abandoned her and vanished.

Mohn’s subsequent complaint to authorities, with details on how her “partner” operated, suggested that Allen Steven Klein may well have been Bernard Frederick Champagne.

On April 10, a warrant was issued for his arrest, adding to the list of previous indictments, but also triggering an intensified FBI manhunt. And this time, Bernard’s luck finally ran out when several FBI agents from the Cleveland branch arrested him in Dalton. At his arraignment the next day in Canton, Ohio, Champagne did what he had always done in the past—pleaded guilty.

Hoover addressed the media, mentioning several of the personas Bernard had assumed, including that of FBI agent. The Director noted, “Champagne operated from coast to coast, leaving a trail of disillusioned women who gave him sums ranging up to $4000 [$52,000 in 2013].”

Though his documented crimes may have been the proverbial “tip of the iceberg,” an aura of mystery surrounded Champagne’s incarceration, much as it had his life of crime. After pleading guilty, he was held under $10,000 bond ($130,000 in 2013) at Cleveland for federal grand jury action. At that point, he seems to have vanished.

Perhaps the FBI avoided publicizing his story any further once he was captured. Champagne had defrauded hundreds of victims out of untold thousands of dollars—certainly the equivalent of millions of dollars today. To the embarrassment of lawmen, he had gotten away with most of it during the past seven years. Heavily redacted records limit our knowledge of his activities.

Despite the vast number of charges pending against Bernard in at least nine cities (for fraud and for impersonating federal officials), the Cleveland grand jury settled on a puzzling set of indictments: “Violation of the Mann Act, in transporting a waitress from Orrville [Ohio] to California via Winter Haven, Florida- violation of the Selective Service Act for not having his registration card with him- and posing as a lieutenant commander in the US Navy with intent to defraud.”

It appears that he served approximately 18 years in prison and was released in the early 1960s, returning to the North Country. Champagne passed away in 1977 at the age of 73.