Religious differences are often the root causes of war, and in 1870 Utah, that’s what dominated politics. Unlike most of the nation, Utah had no Democratic or Republican parties. Instead, it was the Liberals (the anti-Mormons) versus the People’s Party (the Mormons). Eventually playing a fateful role in the outcome was a North Country man, George Montgomery Scott, a successful businessman in the territory.

Religious differences are often the root causes of war, and in 1870 Utah, that’s what dominated politics. Unlike most of the nation, Utah had no Democratic or Republican parties. Instead, it was the Liberals (the anti-Mormons) versus the People’s Party (the Mormons). Eventually playing a fateful role in the outcome was a North Country man, George Montgomery Scott, a successful businessman in the territory.

The anti-Mormons made gains over the years, particularly in Tooele County, which became known as the Republic of Tooele when residents voted the Liberals into power for a five-year period. During that time, it created an odd situation. Tooele leaders, under the Liberal flag, instituted women’s suffrage.

While suffrage may have worked well in Tooele County, the Territory’s Liberal Party was forced to oppose the measure. Independent women might vote their own minds, but the Mormons already practiced suffrage, which added to their power because the Mormons generally voted as a bloc.

Anti-Mormons gained small victories here and there, gaining a more solid footing. Dramatic changes in the character of the population aided their cause. By the late 1880s, it was estimated that Salt Lake Mormons had been reduced from 90 percent to about 50 percent of the city’s head count.

The bitter battle came to a head in the 1880s with the aggressive enforcement of new laws against polygamy. Within that atmosphere, the fight against religious rule was won in several more communities. While it may have had a political face, the conflict was between two sets of church beliefs.

The ultimate seat of Mormon power, Salt Lake City, had remained untouchable for four decades. What many saw as the death knell of Mormon political control came in 1890. The results were touted across the country as the most important election of the year. For the first time, Salt Lake City had elected a non-Mormon mayor.

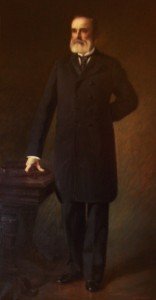

The victor was George Montgomery Scott, born and raised in Clinton County, New York. It was a prodigious victory, creating hundreds of media headlines.

With Scott assuming control in what had long been the Mormon center of power, change came swiftly to both sides. Latter Day Saints President Wilford Woodruff soon issued the Woodruff Manifesto, forever revising church doctrine with the line, “I now publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land.”

With the grudging acceptance of federal marriage law by the official church, the crux of the problem was suddenly gone. The Mormons, always politically astute, disbanded the Peoples’ Party within a year and directed its followers to the nation’s two major national parties, Democrats and Republicans.

The Liberals were slower to move, but did the same two years later. Since that time, the Mormons have always held great sway in Utah politics, but well short of the control they once tried to parlay into a Vatican-like theocracy. No matter how great your god is, that’s a tough sell in a democracy.

The newly elected mayor of Salt Lake City was virulently anti-Mormon and a devout Episcopal, reflecting one facet of the religious war that shook the West. A number of issues ruled Utah’s early development, but a prominent theme was “my god is better than your god,” the basic foundation of so much strife in the world’s history. In Utah, the god issue came to a head over the concept of plural marriage.

George Montgomery Scott commanded center stage for only two years. The mayoral run was his only foray into politics in a career devoted principally to the world of business and community development. He was a commissioner of the 1883 World’s Fair, treasurer of the Utah Eastern Railroad, a founding member of the Utah Stock Exchange, and supported Episcopal hospitals and churches. His election victory, once the biggest news in the nation, is now a footnote in history

Due to illness and age, Scott sold his business interests in 1904 and retired to California. He died of pneumonia in San Mateo in 1915.

Photo: George Montgomery Scott.