During battles for the presidential nomination, a candidate’s faith has sometimes been an issue, with the intention of fostering fear or negative feelings about a candidate whenever the religion is mentioned.

During battles for the presidential nomination, a candidate’s faith has sometimes been an issue, with the intention of fostering fear or negative feelings about a candidate whenever the religion is mentioned.

In 2012, one target early on was Mitt Romney and the Mormon religion. It’s interesting that fear and loathing of Mormons coming to power is not a new thing. In the 19th century, when they dominated life in the Utah Territory for several decades prior to statehood, a fierce battle was waged between two religious factions.

Many factors came into play before things were finally resolved. In one of the climactic moments that helped eliminate a powerful theocracy, a North Country man ended the Mormon’s 43-year rule of their greatest bastion, Salt Lake City.

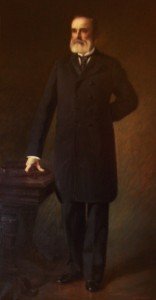

George Montgomery Scott was born in July 1835 in Chazy, New York. From northern Clinton County, he moved West during California’s gold rush. In San Francisco, he established a successful hardware business, supplying the tools of the trade to hundreds of miners.

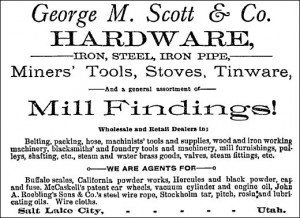

In 1871, in pursuit of new opportunities, Scott moved to the Utah Territory, where many mines were in early development. Besides investing in the Crystal Gold and Silver Mining Company, he also established the very successful George M. Scott Hardware in Salt Lake City.

As a member of the Lily Park Stock Growers Association in Colorado, he frequently dabbled in horses and range stock. In one transaction alone, Scott purchased 60 rail cars of cattle (over 1000 head). The man obviously had plenty of money. Known as one of Salt Lake City’s leading businessmen, he traveled in first-class accommodations to several states and territories on business and pleasure trips.

The downside among all this financial success was Utah Territory’s political atmosphere. Non-Mormons had virtually no voice in government because Mormons (a very high percentage of the population) were strictly bound by church rules, which applied to their entire lives, not just their religious activities. They generally voted as a bloc, which gave them absolute control of government. And unlike federal law, they allowed suffrage, in effect doubling their voting power.

When the US expanded westward, winning the Mexican-American War added vast new territory to the nation. Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City grasped the opportunity to firmly establish a power base. Statehood was applied for under the name Deseret. Had they been successful, the newest American state (Deseret) would have encompassed modern-day Utah, most of Arizona and Nevada, plus parts of California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, and Wyoming. Officers were elected to represent Deseret, led by Governor Brigham Young.

When the US expanded westward, winning the Mexican-American War added vast new territory to the nation. Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City grasped the opportunity to firmly establish a power base. Statehood was applied for under the name Deseret. Had they been successful, the newest American state (Deseret) would have encompassed modern-day Utah, most of Arizona and Nevada, plus parts of California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, and Wyoming. Officers were elected to represent Deseret, led by Governor Brigham Young.

At the federal level, the State of Deseret’s application was denied because of two main issues: the proposed size was too large, and the controversial policy of polygamy was incompatible with American law. Since Mormon rules governed people’s religious and civil life, Washington legislators were doubtful about their future adherence to the laws of the land. Technically, the denial came because the area fell short of one requirement for statehood?a minimum population of 60,000.

The application was modified in 1850 to embrace what became known as the Utah Territory, and with congressional and presidential approval, Brigham Young was appointed as governor.

During the next four decades, at least six applications for Utah statehood were denied. There were many impediments, but the territory had become a virtual theocratic state controlled by the Mormons. Added to that was the ultimate deal-breaker: polygamy. To the adherents of other religions, plural marriage made Mormons nothing more than heathens.

For decades, the struggle for control of the Utah Territory was much more a religious battle than a political one. Progress was slow, but the non-Mormons made inroads, supported by federal laws outlawing bigamy, and the president’s official removal of Brigham Young as governor in 1857.

Young resisted the presidential order and prepared to fight when federal troops were dispatched (the standoff became known as the Utah War, although no battles were actually fought). It is testament to Mormon power that, despite the setbacks, they maintained control of the territory for three more decades.

One reason for that dominance was revealed by a simple head count. In 1870, Salt Lake City’s population was about 90 percent Mormon, a number that would gradually decline during the great western migration.

Next week, the conclusion: A religious/political party battles for power.

Photos : George Montgomery Scott- Advertisement for Scott’s hardware store.