In the 1830s, hundreds of inventors around the world focused on attempts at automating farm equipment. Reducing the drudgery, difficulty, and danger of farm jobs were the primary goals, accompanied by the potential of providing great wealth for the successful inventor. Among the North Country men tinkering with technology was Eliakim Briggs of Fort Covington in northern Franklin County.

In the 1830s, hundreds of inventors around the world focused on attempts at automating farm equipment. Reducing the drudgery, difficulty, and danger of farm jobs were the primary goals, accompanied by the potential of providing great wealth for the successful inventor. Among the North Country men tinkering with technology was Eliakim Briggs of Fort Covington in northern Franklin County.

Functional, power-driven machinery was the desired result of his work, but while some tried to harness steam, Briggs turned right to the source for providing horsepower: the horse.

This particular branch of the Briggs family had many members across New England, descended from Irish ancestors who fought in America’s Revolutionary War. A number of them later moved to New York in southern Washington County, which is where Eliakim was born in 1795.

Dozens of Vermonters and eastern New York State residents were among the first to move farther north and settle along the border with Canada from Clinton County to western Franklin County. Several members of the Briggs clan, including Eliakim, made the journey around 1820.

With a background in foundry work, young Eli began experimenting with building a “traveling threshing machine.” Around this time, he married Chateaugay’s Russina Allen (a descendant of Vermont’s Ethan Allen), who had moved there from Ticonderoga. They settled in Fort Covington, and by 1827, Russina had given birth to five children. Only the fifth, Janette, survived infancy.

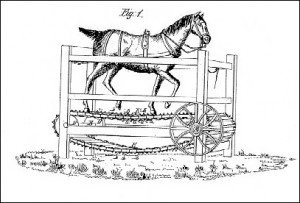

Eli’s inventive efforts proved successful, and he began patenting his creations. Unfortunately, a fire in December 1836 destroyed 80 percent of the Patent Office’s 10,000 records. Among the documents to survive were those covering Eliakim’s “Horse Power Machine” (patented July 12, 1834), and his machine for “mowing, thrashing, and cleaning grain,” patented February 5, 1836.

The 1834 machine was an improvement in design and function of the existing horse treadmill, which was subsequently used to power his threshing machine. Looking to the future, Briggs perceived all sorts of possibilities from harnessing the power of horse-driven treadmills.

In the following year, on the Saratoga &- Schenectady Railroad (one of New York’s very first rail lines) was a most unusual sight. Instead of the customary single rail car being towed along by a horse, the car was moving silently forward with no visible means of propulsion.

Gawkers could hardly believe their eyes, but the secret lay within, where a horse on a treadmill propelled the car forward at the then blazing speed of 15 miles per hour, prompting one reporter to observe, “This is indeed an age of wonders.” He was witnessing the handiwork of Eliakim Briggs of Fort Covington, whose remarkable invention was being manufactured and sold in Ogdensburg at the time.

Briggs believed that the greatest potential for financial success was in agriculture, and after a trip to the West (which was Indiana, since there were only 26 states at that time), he was convinced. The family pulled up stakes and relocated to Dayton, Ohio.

In 1839, Thomas Clegg, one of Dayton’s pioneer industrialists, operated the Washington Cotton Factory, which had an extensive machine shop. Clegg partnered with Briggs in producing his automatic threshing machine, to the great financial benefit of both men.

Eliakim became one of the leading entrepreneurs of Dayton, but after three years, he moved on to Richmond, Indiana for a year. In 1841, the family resettled in South Bend, and it was there where Eliakim really made his mark. The fledgling settlement of perhaps 700 citizens soon experienced rapid growth, driven in part by Briggs’ threshing manufactory (powered by windmills), one of the first industries in the town’s history.

After three years of success, the company outgrew its quarters. Briggs built a large new factory, providing employment for many residents, some of whom later became leading businessmen themselves (the famed Studebakers are one example).

Briggs’ traveling threshing machine was a big success, and not only because of the inventor’s great abilities. Eliakim’s charisma was evident in his open, friendly treatment of customers who came from Indianapolis, Lafayette, Richmond, and other western locations. He opened his expansive home to visitors and customers alike, earning a reputation far and wide as the most hospitable and generous of businessmen.

He also remained a family man to a brood that had grown to nine by 1844, including sons John, George, and Charles, who eventually followed business pursuits as aggressively as their father had. John caught gold fever and ventured to California in 1849. As his brothers became old enough, they joined him in several business exploits, including mining. One part of their legacy, still producing gold today, is the Briggs Mine, about 20 miles north of Denver.

Successful in business, Eliakim combined his personal beliefs with financial profits in pursuit of a personal passion: the anti-slavery movement. He was a fervent abolitionist who sought freedom for all. Briggs abhorred slavery and was a longtime, ardent supporter of the Underground Railroad, despite the inherent dangers.

In early 1861, at the age of 66, Eli was still securing patents on new devices, while his horse-driven machines remained very popular. That same year, previous failures in the effort to process sugar cane in the West finally met with success when new equipment was introduced: “…a horizontal, three-roller, horse-power press for expressing the juice, manufactured by E. Briggs of South Bend, capable of pressing out sixty gallons per hour …”

Eventually, the development of steam and other power sources would replace Eliakim’s creation, but during his lifetime, it remained an important component of industry.

Briggs died in September 1861, still successful in industry, and still battling for the abolition of slavery. A year later, in September 1862, his wife, Russina, passed away as well. Much of the family fortune was placed in the hands of daughter Janette, a widow whose husband had also done quite well for himself.

Janette became very well known for philanthropy in South Bend. When she died in 1916, several bequests were included in her will, including $15,000 to an orphanage and $12,000 to the YWCA. Those two bequests alone were equal to approximately $500,000 in 2013, reminiscent of the generosity her father exhibited throughout his life.

Photo: Patent drawing of Eliakim Briggs’ horse treadmill (1834).