It now seems hard to believe that for most of the latter part of the 19th century, New York City was the cigar making capital of the United States.

It now seems hard to believe that for most of the latter part of the 19th century, New York City was the cigar making capital of the United States.

New York State as a whole had 364 cities and towns with 4,495 cigar factories and 1,875 (41%) of these were operating in mid and lower Manhattan. The island which then comprised the City, made 10 times the number of cigars as Havana, Cuba.

At the city’s peak before WWI and the beginning of the Machine-Age, approximately 3,000 factories, including many of America’s largest, rolled cigars in Manhattan.

In fact, the 2nd and 3rd Tax Districts of New York were the only such districts in the country to be located entirely within the boundaries of one city. Although cigars rolled in Manhattan’s 3rd District were responsible for a high percentage of the cigar industry, other New York cities with significant cigar output included Albany, Binghamton, Brooklyn, Buffalo, the Bronx, (then part of Westchester County) Rochester and Syracuse.

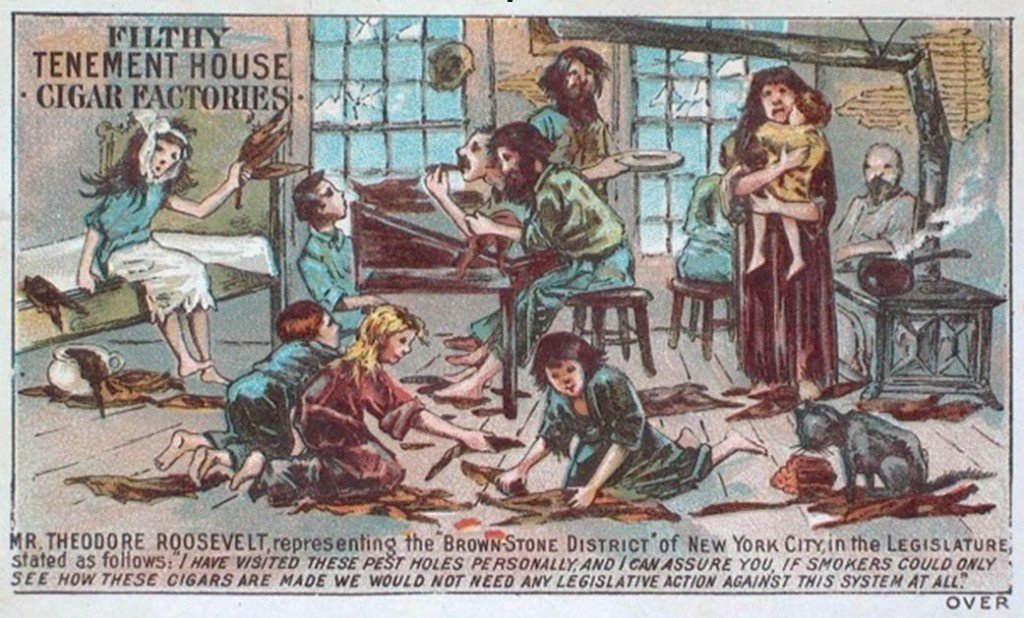

In New York City, rollers working in their own tenement apartments used them as cigar-making workshops. As of 1883, cigars were manufactured in 127 apartment houses in New York, employing 1,962 families and 7,924 individuals. A state statute banning the practice, passed late that year at the urging of trade unions was ruled unconstitutional less than four months later.

Historically cigar making in the city began well before the Revolutionary War and by 1894, there were around 3,000 such establishments and close to 500 of these, were Hispanic owned. When Bernardo Vega, a young cigar roller from Cayey, Puerto Rico arrived in the city in 1917, the overall number of cigar making establishments had dwindled to the hundreds and only a few dozen were Hispanic owned.

Some of the Hispanic-owned business had been in New York City, Philadelphia, Key West, Tampa and several other U.S. mainland cities since the mid 1800s. Around this time, many Cuban and Puerto Rican cigar-rollers who were in the forefront of attempts to liberate their respective islands from Spanish rule became exiles. Initially, these political refugees sold their cigars to their emigre brethren but as time went by their cigar-making expertise created a demand outside of their insular communities and they survived by subcontracting to the larger, non-Hispanic cigar making establishments.

These new larger factories were also (in part) the unintended result of Samuel Gompers and the establishment of the Cigar Makers International Union (CMIU) that he founded to protect the wages and other interests of cigar rollers. Until the arrival of the CMIU, most rollers and other related tobacco product workers worked in their own, dingy tenement apartments and Gompers was determined to stamp out this practice.

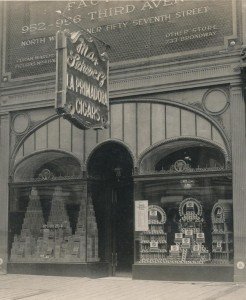

However, not all home-based and small cigar-making business were eradicated and some of the smaller factories and shops that survived were owned by Spaniards, Cubans and Puerto Ricans and it was in these, that Bernardo Vega found a job. At first, he went to work at Fuentes &- Co. located on Pearl and Fulton Streets in lower Manhattan but he soon quit when they marked down his vitola—the shape and size of cigar-that he specialized in. Traditionally, all cigar makers were paid by the piece, so much money per thousand cigars and each torcedor or tabaquero had his own vitola as indicated on the cigar ring. Fortunately, Bernardo was able to find another cigar-rolling job at El Morito –the Little Moor, on East 86th and Third Avenue. Here he became fast friends with many of the Cubans, Dominicans, Spaniards and Puerto Ricans cigar makers who made him aware of the issues and concerns of Hispanic torcedores in New York who had been marginalized in the industry even though they arguably were among the finest cigar craftsmen in the world. With their skill and presence, coupled with their knowledge of the legendary Cuban tobacco grown in the Vuelta Abajo region of the Pinar del Rio Province, New York was positioned to be the leading U.S. city in terms of the quantity and quality of American made cigars.

On top of the quality-scale stood the “Clear Havana” (light tan colored cigars) which used tobacco from the Vuelta Abajo Region just to the east of Havana. Interestingly enough, the seed for these was originally grown in Puerto Rico. However, “Clear Havana Cigars (needless to say) was first produced in Cuba and was so successful that by the 1840s, it replaced coffee as that nation’s top export.

Back in the day, Hispanic-owned in the U.S. establishments ranged in size from a chinchal (workshop employing a master cigar maker and to or three apprentices) to fabricas (factories employing 50 to 100 workers.) These two categories usually employed only men and engaged in all phases of cigar making but some of the fabricas called despalillados employed mostly women who stripped the stems from the tobacco leaves.

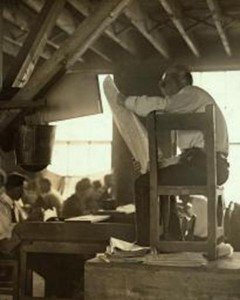

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Hispanic cigar making process was the presence of a lector or reader at the factory perched on a jury-rigged platform. From there, he read (aloud) to the torcedores at work on their benches below in the manner of a storyteller, from newspapers, novels and other works. Astonishingly, he was not paid by the owners but by the workers themselves who paid him in cigars, which he in turn sold.

Usually, the morning hours were devoted to the current news and affairs of the day gleaned from newspapers and the latest wireless news bulletins to which he had access. The afternoons were dedicated to more serious readings from political or literary books and other sources. In the manner of present day book clubs, a committee on readings selected these publications and all the workers voted on their recommendations.

The selected readings by and large were from the classics of such authors as Cervantes, Dostoyevsky, Dumas, Gothe, Hugo, Unamuno and such lesser known but important Hispanic writers like Loti, Perez Galdos, Vargas, Vila and others. Also read aloud were the more political tracts of Engels, Marx and other communists, socialists, radicals and anarchists. Additionally, poetry an inconceivable choice on the floor of an American factory or for that matter, in any workplace, but it was the norm in tabaquerias. A reader in a cigar factory in Tampa, Florida, photographed by Lewis Wickes Hines, 1909. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

American factory or for that matter, in any workplace, but it was the norm in tabaquerias. A reader in a cigar factory in Tampa, Florida, photographed by Lewis Wickes Hines, 1909. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The practice of readings began in Cuba around 1864 in the factories of Vinas &- Co. located in the town of Bejucal where the idea of placing the lector was also initiated. Legend has it that the practice began much earlier in a Cuban prison where an enlightened warden allowed a literate prisoner to read various works to preoccupy the inmates. Cuban cigar makers brought the pra

ctice to Key West and Tampa. In New York, Puerto Rican cigar rollers who had been in the city since the mid-1860′-s, further expanded the use of readers. As far as is known, this fashion never took hold in the largely English-speaking shops and factories although Samuel Gompers did try to introduce it.

“These factory readings which were followed by animated discussions on what was read. Although these group discussions were not formerly led, it was assured that everyone who had a point of view could make it and if some controversy could not be resolved, an arbiter, usually one of the more educated workers, would be called upon to resolve it. Additionally, if someone disputed names, dates or other question of facts, he was required to go to the mataburros —- donkey slayers, as reference books were called. It was not uncommon for someone to go to the public library and consult an encyclopedia or other reference work to prove, or disprove, a point, [just like Google is used today] Many a pelea de perros–dog fights, were resolved in this fashion. They might not have had much formal education, but through the medium of the lector, the Hispanic cigar-rollers were surely the most well informed members of the. American labor movement. and, they were known as the “intellectual proletariat.” – Bernardo Vega, Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A contribution to the history of the Puerto Rican community in New York, (Monthly Review Press, New York, 1984)

The readings were not mere entertainment. They had a very pragmatic intent- to generally educate the cigar workers, to keep them in touch with the political currents of the day, to raise their social consciousness, to foster the discipline and timing of the artisan’s job and most important of all, to achieveme economic well being, respectability and social equality. However, most every attempt to use their intellectual skill to organize and gain the high status they desired foundered. Apparently they could not to bridge the racial, cultural and linguistic gap between themselves and the American labor movement, namely the Cigar Makers International Union an almost exclusively white ethnic organization.

Additionally, internecine warfare was the norm among the tabaqueros, the most socially conscience and independent minded workers of the cigar making community. The CMIU (at least in New York City) was essentially made up of workers of German and Eastern European ancestry In any event, these European ethnics, long resident in the U.S. conducted their affairs in English.

Ethnicity, language, race, system of work, politics and gender were divisive factors among the cigar-maker workforce of the 19th century and in 1875, Local 144, adopted a policy of high dues and the elimination of separate language sections. These and other measures including their campaign tended to eliminate tenement labor shops where most Hispanics and other more newly arrived immigrants and women were concentrated created the gulf. Nationwide, the CMIU was in the main, an organization of white male cigar rollers. The CMIU did have one black local in Charleston, South Carolina, and another in New Orleans, Louisiana, but it actively resisted the creation of a Filipino-Chinese local in San Francisco, California.

In any case, the majority of Hispanic cigar makers in New York and in Florida remained apart from the more mainstream CMIU. In Florida, Hispanics organized the “Sociedad de Torcedores de Tampa y Sus Ceracnias”-Society of Cigar-Rollers of Tampa and its Environs”, better known as the Resistencia. This group admitted all classes of cigar workers, including women who were usually employed as tobacco leaf stem removers. Additionally, Hispanics and the Cubans in particular, made no bones that they regarded themselves as inherently better cigar makers than the largely German-based CMIU members. The hostility between the union and the Hispanics also was due to the fact that Hispanics were more radical and regarded the union as being politically conservative.

Shortly after WW I, in New York, the Trabajadores Amalgamados de la Industria del Tabaco, – Amalgamated Workers of the Tobacco Industry, which was Hispanic dominated was established. It included Jews and Italians and published The Tobacco Worker a bilingual newspaper. The Amalgamados as they called themselves, soon disappeared. As could be expected, they voiced strident criticism of the large-scale mechanized cigar

manufacturers and their system of compartmentalizing the cigar making process and they were labeled as “Bolshevik”.

The hysteria created by the “Red Scare” of 1919 in part, finished them off. Many of the non-citizen torcedores were jailed and deported back to Spain and Cuba when some14 Amalgamado leaders of were implicated in an alleged “anarchist plot” to assassinate President Wilson. They were later exonerated, but the damage had been done.

However, far more devastating was the post war depression. As more and more of the small independent cigar shops where Hispanics were concentrated foundered, they unable to compete with the mechanized, larger factories, and they lost more and more jobs. Finally, the popularization of cigarettes as the tobacco product of choice of Americans dealt a knock-out blow.

Once, the torcedores were the highest paid members of the Hispanic working class of the city and as such, the pride and economic mainstays of their community. Their traditional, hand-made cigars and individualistic vitolas, gave way to machine-made, cheaper and lower quality products.

Today, the five hundred Hispanic cigar-making shops that once existed in New York City in 1894 are down to a few. These are: La Rosa Cubana, at 862 Avenue of the Americas (aka Sixth Avenue) between 30th and 31st Streets and at 37A Seventh Avenue, between 12th and 13th Streets, P.B. Cuban Cigars, at 137 West 22nd Street between Avenue of the Americas and Seventh Avenue, Martinez Cigar at W. 29th and 7th Avenue and Taino Cigars 93-99 Nassau Street, at the corner of Fulton Street.

What a fascinating article. And how appropriate as I’m into the thick of reading about cigar making in the US, not something I would have thought I ‘d be delving into, though it’s for research associated with a work of narrative nonfiction concerning the turn of the 20th century in New York City –about the suffrage movement and pockets of organizing for other social issues, cigar making being one of them. This was a pre-cigarette era and the mechanization hadn’t yet been developed for this upcoming enormous industry. Apparently many cigarmakers’ union locals were ethnic pockets of skilled cigar craftsmen from small villages all over Europe, mostly men. So far I’ve read only Tampa and the cigar makers there, so this article focusing on New York City was a breath of fresh air. And timely for me. I love the part about the factory readers.

Thanks Margarite. Initially the Hispanic cigar rollers were men and the women (and children)were relegated to tearing the tobacco leaves from the stems. However by then end of the 19th century women moved up in the cigar making hierarchy. I will consult my list of cigar factories to see if there were any women who owned shops and let you know. Anyway. the Hispanic version of the Cigar Twisters Union did admit women into their ranks and I have seen pictures of women readers in modern day Cuba. In case you you have not consulted it there is a good book on this Called ONCE A CIGAR MAKER: Men, Women, and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900-1919 (Working Class in American History) [Paperback] by Patricia A. Cooper. Also recommend: El Lector: A History of the Cigar Factory Reader [Paperback] by Araceli Tinajero and a paper put out by Prof Stephanie L. Maatta, Ph.D El Lector’s Canon: Social Dynamics of Reading from Havana to Tampa. conference.ifla.org/past/ifla77/81-maatta-en.pdf