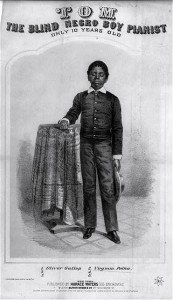

In June 1874, music lovers in Northern New York were excited. For the second time in three years, Blind Tom, the world-renowned black pianist and entertainer and arguably the first black superstar to perform in the U.S., was coming to Malone. For years after the Civil War, he had been wowing audiences throughout the U.S., Great Britain, Canada, continental Europe, and South America with his one-man show which was part vaudeville and part classical piano music.

In June 1874, music lovers in Northern New York were excited. For the second time in three years, Blind Tom, the world-renowned black pianist and entertainer and arguably the first black superstar to perform in the U.S., was coming to Malone. For years after the Civil War, he had been wowing audiences throughout the U.S., Great Britain, Canada, continental Europe, and South America with his one-man show which was part vaudeville and part classical piano music.

Tom had many talents including the ability to: play the piano, coronet, French horn and flute- sing and recite speeches of well-known politicians in Greek, Latin, German and French- mimic any music a member of the audience might offer for him to hear- and use his voice to make the sounds of locomotives, bagpipes, banjos and music boxes. While singing one song, he could play a second with his right hand, and a third with the left.

During the serious part of the show, he often would play Liszt fantasies, Beethoven sonatas, and Bach fugues. Tom’s repertoire also included popular music of the day as well as his own musical compositions – he is reported to have written 100 of them. His most popular titles were: “The Rain Song,” “The Battle of Manassas,” and “The Sewing Song: Imitation of the Sewing Machine.” Contemporary reviewers often compared him to Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin.

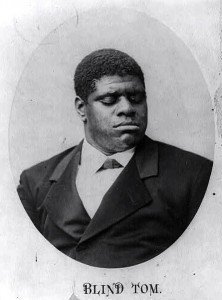

Thomas Greene “Blind Tom” Wiggins was born blind, possibly autistic, and a slave in Georgia on May 25, 1849. When he was four, his master’s family noticed his ability to mimic the sounds he heard and play back piano music performed by family members. They gave him piano lessons and by the age of six, Tom was composing his own music. When Tom turned eight, he made his debut as “Blind Tom” in a concert hall rented by his slave master in Columbus, Georgia. After receiving rave reviews following his performance at the University of Georgia later that year, his musical career soared. Often performing four shows a day, he became a megastar. He entertained enthusiastic audiences for the next 50 years including a performance at the White House for President James Buchanan in 1860. Tom died from a stroke in New Jersey on June 13, 1908 at the age of 59. He was buried in an unmarked grave at The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Thomas Greene “Blind Tom” Wiggins was born blind, possibly autistic, and a slave in Georgia on May 25, 1849. When he was four, his master’s family noticed his ability to mimic the sounds he heard and play back piano music performed by family members. They gave him piano lessons and by the age of six, Tom was composing his own music. When Tom turned eight, he made his debut as “Blind Tom” in a concert hall rented by his slave master in Columbus, Georgia. After receiving rave reviews following his performance at the University of Georgia later that year, his musical career soared. Often performing four shows a day, he became a megastar. He entertained enthusiastic audiences for the next 50 years including a performance at the White House for President James Buchanan in 1860. Tom died from a stroke in New Jersey on June 13, 1908 at the age of 59. He was buried in an unmarked grave at The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Tom’s concert tours often took him to the major urban centers of New York State. In New York City, he performed at the Academy of Music, Irving Hall, Cooper Institute and Steinway Hall. In Brooklyn he played in the Brooklyn Athenaeum, and in Albany, he performed in Tweddle Hall. On June 14, 1874, Blind Tom, advertised as “the most wonderful living curiosity of the 19th century,” performed in Lawrence Hall in Malone. His advance notices billed him as “the great incomprehensible musical mystery of the 19th century.” They dramatically explained to readers that as if to make amends for his blindness, “a flood of light poured into his brain, and his mind became an opera of beauty written by the Hand of God in syllables of music, for the delight of the world.”

Reviews following Tom’s show in Malone described him as “the great musical conundrum” and noted that “the music just slips off his fingers in chunks.”

Modern musicologists have revisited Tom’s performances and musical compositions. Their articles tend to look past the vaudevillian segments of his act which 19th century critics labeled “freakish” and “idiotic.” Instead, modern music writers praise Tom for being a serious composer and gifted concert pianist. A writer for The New York Times went so far to say that Tom is “the most celebrated black concert artist of the 19th century.”

In 2000, John Davis, a New York pianist, released a CD of 14 of Tom’s compositions. Davis became so interested in Tom’s life, he located where Tom’s grave was on Pleasant Hill in The Evergreens Cemetery and arranged to have a tombstone placed on it. The inscription reads, “Renowned pianist and composer who performed in the White House before President James Buchanan.”