Tornados in upstate New York, like those that struck recently in the Capital Region, are comparatively rare events, but are by no means anything new. Similar storms in the past have wreaked devastation in New York and New England, but few have had the incredible impact of the twister that struck northern Franklin County on June 30, 1856. The results bore strong similarities to the recent destruction near Oklahoma City.

Tornados in upstate New York, like those that struck recently in the Capital Region, are comparatively rare events, but are by no means anything new. Similar storms in the past have wreaked devastation in New York and New England, but few have had the incredible impact of the twister that struck northern Franklin County on June 30, 1856. The results bore strong similarities to the recent destruction near Oklahoma City.

The storm system caused chaos across the North Country, in lower Quebec, and in northern Vermont as well, but the villages of Burke and Chateaugay in New York bore the brunt of the damage when a tornado touched down, causing destruction of historic proportions.

In the 1850s, northern Franklin County was mostly a vast, wooded wilderness. The arrival of the railroad had led to accelerated growth and the development of several population centers, including Burke and Chateaugay, just five miles apart in the county’s northeast corner.

Farming and lumbering were the chief occupations, and until sections of forest were cleared, most of the farms were located near the villages and along the Old Military Turnpike (modern-day Route 11). About the only way a storm’s effect could be truly devastating was for it to strike the population centers—and that’s exactly what happened.

Not that it would have made much difference, but this storm also had an extra element of surprise—it struck shortly before mid-morning. The great majority of tornadoes strike in the late afternoon after the sun has had plenty of time to heat things up.

Farmer Lucas Wyman of Constable watched as two dark, threatening cloud systems moved towards each other, one from the southwest and one from the northwest. He described their meeting as a thunderous collision, after which the storm began devouring everything in its path. Taking a northeastern track, it flattened trees and fences as it sped ominously towards Burke.

Arriving at the village, it tore the roofs off several buildings, sending their contents high in the air to parts unknown. As the storm raged, only pieces of some homes were left standing, and all barns, less sturdily built by their very nature, were leveled.

Arriving at the village, it tore the roofs off several buildings, sending their contents high in the air to parts unknown. As the storm raged, only pieces of some homes were left standing, and all barns, less sturdily built by their very nature, were leveled.

At the hamlet of Thayer’s Corners, the store of Daniel Mitchell was completely destroyed. Thirty-six-year-old Jeremiah Thomas, father of two young children, had recently sold his farm and gone to work for Mitchell. Thomas became the storm’s only fatality.

The storm’s route from Burke to Chateaugay suffered near-universal destruction, with reports indicating that “… 185 buildings, either unroofed, blown down, or moved from the foundations, can be counted as you ride along the road.”

At Chateaugay, the twister still had more than enough energy to lay nearly the entire community to waste. One reporter stated it plainly: “The village of Chateaugay is a complete desolation. Not a building escaped injury, and a great number—we do not know how many—are completely destroyed. The scene is one which baffles description. Stores, churches, dwellings, barns, sheds, outbuildings, all present a sad spectacle —they are awfully shattered and broken to pieces.”

Perhaps as important were other losses—gardens and fruit trees destroyed- farm crops flattened- cows, pigs, horses, sheep, and chickens killed. With all fencing destroyed, any animals that survived were left wandering the countryside.

Though only one person died, many suffered serious injuries. Dozens were struck by flying roof shingles and shards of glass. One survivor was said to have lost his scalp to airborne debris.

The power of the storm yielded the usual stories of extreme occurrences. Entire sections of forest were flattened. A stone schoolhouse, one of the more solid buildings, was demolished. A lumber yard was completely devoid of lumber, all of which had been lifted high in the air and strewn across nearby fields.

A railroad handcar, weighing about a ton, was destroyed when it was carried aloft and dropped into the nearby woods. The tornado’s power was such that rubble from Mitchell’s Store at Thayer’s Corners was later found ten miles east in the town of Clinton.

In the days following the catastrophe, a traveler from Springfield, Massachusetts, rode the train across northern New York. After encountering the Chateaugay area, his report on the damage was published in the Springfield Daily Journal, including the following excerpts.

“The railroad track for some thirty or forty miles lies directly in the path of the tornado, and I never saw such a scene of destruction before. … it is in fact quite impossible to picture the scene on paper as it really appears. The villages of Chateaugay and Burke have sustained such serious damage that long years will come and go before its traces can be effaced.

“The railroad track for some thirty or forty miles lies directly in the path of the tornado, and I never saw such a scene of destruction before. … it is in fact quite impossible to picture the scene on paper as it really appears. The villages of Chateaugay and Burke have sustained such serious damage that long years will come and go before its traces can be effaced.

“… Acres of forest trees are upturned, broken, twisted, and shattered- fences are torn to pieces, and the fencing timber scattered miles away from whence it was taken- piles of lumber, with which that section abounds, are nowhere to be found- barns are entirely blown to pieces- dwelling houses blown down, unroofed, and shattered. The eye rests on nothing else but such sights as these for miles and miles.”

The storm system caused considerable damage elsewhere, but the extent of destruction along the eight-mile path through the towns of Burke and Chateaugay was of near-Biblical proportions. In the final tally, 364 buildings were damaged or destroyed.

Few North Country disasters can compare in scope and intensity with the tornado of 1856. For decades into the future, it was used as a reference point for comparing other tragic events.

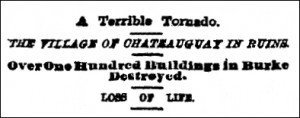

Photos: Top?Tornado headlines (1856)- Middle?St. Lawrence County opportunistic ad after a tornado (1914)- Bottom?Hammond Insurance ad for routine needs (1935).